By DAVID W. DUNLAP

Lens has shared this story with Der Spiegel, the leading German newsweekly, and Spiegel Online, its Web edition. We hope readers of Spiegel’s EinesTages site (Once Upon a Time) can help solve a 70-year-old mystery: Who created this photo album of the Eastern Front?

There are certainly many photo albums of Nazi leaders and many photo albums of the Nazis’ victims. But it’s hard to imagine many albums depicting both, just a few pages apart.

At least one does, however, and it has surfaced in New York City. Its creator was able — apparently within weeks — to photograph Hitler as he warred on Russia and also to photograph some of the earliest victims of that brutal campaign, known as Operation Barbarossa, which began 70 years ago Wednesday.

Two pages in this album, on the Eastern Front in 1941, are devoted to prisoners. Some are dressed in rags, some dressed in uniforms of the Red Army, some wearing jackets with Star of David patches. They stand before what might be freshly dug graves. (Their own? Their landsmen?) In six almost intimate pictures, verging on portraiture, men gaze hollowly or defiantly at the camera.

Four pages later, there is Hitler himself, waiting at a train station for the arrival of Adm. Miklos Horthy, the regent of Hungary, with whom he will shortly be bargaining at the East Prussian war headquarters known as the Wolf’s Lair. The photographer stands just a few feet from Hitler, almost as close to the Führer as he stood to the Führer’s prisoners.

Clearly, this photographer had a lot of access — and not a little talent.

But who was he? His perfectly ordinary, store-bought album carries no identification or inscription. A caption is visible on only one of the 214 three-by-four-inch photographs.

And what was he showing to posterity?

Private collection,

via The New York TimesPage 11: Bus window.

First and foremost, he documented the progress through Eastern Europe of a bus convoy in the service of the Reichs-Autozug Deutschland, a Nazi Party unit whose responsibilities included the logistics needed to stage mass rallies. Judging from graffiti written on the dusty bus windows, the overall itinerary was Berlin-Minsk-Smolensk-Munich. Identifiable landmarks in the album show that the convoy made its way through Gdansk, Poland, which was then Danzig; Kaliningrad, Russia, which was then Königsberg; and Barysaw, Belarus.

Little of the battlefield is seen (the front was, by then, far ahead), but a great deal of destruction is evident. Minsk, the capital of what was then the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic and fell within days of the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, is in ruins. There are many views of the countryside, as well as pictures of peasants that bring the work of the Farm Security Administration photographers to mind.

The central figure in the album; presumably the photographer himself.

Private collection,

via The New York Times

After the interlude with Hitler, the photographer is found recuperating in some kind of convalescent home. He holds his medical chart up to the camera, but it’s impossible to read. From there, it is on to Bavaria, where a motorcycle squad seems to be staging a display of its prowess. Finally, in and around Munich, the photographer is reunited with a pretty woman who may, or may not, be his wife. Or sister. Or mistress.

So many mysteries remain. We’re hoping that the readers of Lens and the Spiegel Online siteEinesTages (Once Upon a Time) will help us unlock this highly personal and quite professional wartime chronicle.

The album is owned by a 72-year-old executive in the fashion industry who lives in New Jersey and works in the garment district of Manhattan. He lent it to The New York Times in the hope that press coverage — and a better sense of the album’s provenance — would increase its value. He would like to use proceeds from a sale, which he hopes will be “six figures or higher,” to pay medical bills and get out of debt. He has undergone quadruple bypass surgery and has declared personal bankruptcy. Not all of his colleagues and competitors know that, or that he owns such an album, so he requested anonymity.

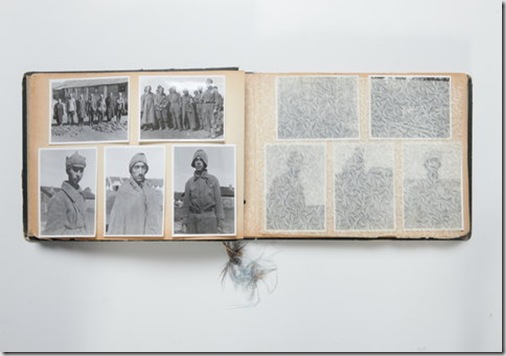

Tony Cenicola/The New York TimesThis album, which surfaced recently in New York, shows the Eastern Front and Bavaria.

He said the photo album and 50,000 baseball trading cards were given to him by a manual laborer of his acquaintance who had fallen on hard times and had to borrow money from the executive. The objects amounted to repayment of the cash loan. The executive said the worker told him he had received the album from an old German man whose lawn he had maintained. Because there are nine pictures of Hitler in the 24-page album, all who handled it were sure it must have some value.

“I knew I had a part of history,” the executive said, “and I was very troubled about it falling into the wrong hands. But my needs are great.”

We accepted the detective assignment with the understanding that we would make our conclusions public even if they undermined the value of the album. And we told the executive that we would not ask any expert to hazard a guess as to the album’s monetary value.

Our only interest was in presenting readers with some astonishing close-up pictures of a great turning point in the Second World War — and in solving a historical puzzle.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 7: Somewhere in Belarus.

We turned first to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“This album differs from most other albums in the quality of the photos,” said Judith Cohen, the director of the photographic reference collection at the museum. “The photographer was clearly a professional and knew what he was doing. It is possible that it is a personal album of a PK photographer.”

The PK, or Propagandakompanie, was the field unit of the Wehrmacht’s propaganda corps. So that alone was a valuable lead. But Ms. Cohen offered an even more important clue. One of the prison pictures in the album (Slide 3) turned out to be identical to photograph No. 1907/15 from the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive, in the collection of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, in Jerusalem.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 8: At a prison camp in Minsk.

That pinpointed the location of the prison camp in Minsk and fixed the year at 1941. It established that the uniforms seen on some of the prisoners — including the distinctively pointed budenovka (Slide 8) — were those of the Red Army. And it brought Daniel Uziel, the head of photo collections at Yad Vashem, into the conversation.

“It was quite common for PK commanding officers or even individual photographers to prepare private photo albums,” he said. “These were kept either by the company’s staff or were given to generals, party members, etc.

“The dissemination of PK photography after World War II is a fascinating and only partially researched topic,” Dr. Uziel said. “This is obviously one of those cases where PK photos found their way out of the wartime propaganda fraternity and its related archives. We recently learned that some Jewish historical committees active in Europe immediately after the end of World War II got their hands on copies of such photos.”

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 9: At a prison camp in Minsk. “There are not many photos of marked Jewish P.O.W.’s,” said Daniel Uziel of Yad Vashem, “because usually they were handed over to the S.S. within a very short time of their marking and were duly executed.”

After looking at selected images sent to him by e-mail, Dr. Uziel said, “Although some photos are clearly propagandistic and shot according to official guidelines, most of the photos are typical ‘battlefield tourism’ in nature.” He explained that the vertically cropped pictures of individual prisoners were standard “PK portraits of Soviet P.O.W.s, made along specific regulations and requests by the Wehrmacht and the Propaganda Ministry.”

“I would say that only those clearly marked with the yellow badge are Jewish,” Dr. Uziel wrote. “There are not many photos of marked Jewish P.O.W.’s because usually they were handed over to the S.S. within a very short time of their marking and were duly executed.”

Minsk was not only the setting of the prison camp, but also the city whose bombed-out streets and buildings show up in numerous pictures. That was confirmed when Prof. Larry Wolff of New York University, the director of the Center for European and Mediterranean Studies, recognized the Baroque spires of the Blessed Virgin Mary Roman Catholic Church. The drumlike Opera and Ballet Theater is another unmistakable landmark.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 6: Spires of the Blessed Virgin Mary Roman Catholic Church in Minsk are visible through buildings hollowed out by German bombs.

What was most useful in establishing the album’s time frame was the meeting between Hitler and Horthy in September 1941. It was known even to American audiences through Life magazine, which published a photo that seems to have been taken only inches away from where the PKs photographer stood at the train station where the two leaders met. The setting was Ketrzyn, Poland, then an East Prussian city called Rastenburg, where Hitler had the war headquarters known as the Wolf’s Lair (Wolfsschanze).

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 13: Adolf Hitler and Admiral Miklos Horthy, the regent of Hungary, met in September 1941. Life covered their summit at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters, publishing a picture almost identical to this.

“Here Horthy insisted that the Hungarian expeditionary force be withdrawn from the Russian front, believing that the Russian campaign was virtually over,” said Prof. Istvan Deak of Columbia University. “Hitler gave his consent.”

(Horthy and Hitler were not alone in believing that the campaign was almost over in the fall of 1941, after German troops had made spectacular progress in their advance toward Moscow. But when the juggernaut was stalled by the resistance of Russian citizens and soldiers, and the punishing Russian winter set in, the tide was to turn dramatically.)

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 5: A German front-line military cemetery

.

Only a few names are to be found in the album. Among them are those on the markers of what Dr. Uziel described as a standard German military cemetery established close to the front lines, with a building behind it whose modernity and massiveness suggests Soviet architecture. The names that are legible include:

Ogefr. (Senior corporal) Gust. Dumke, Flieg. (Air Force private) Fried. Gebhardt, Kf. (Driver) Kurt Henze, Gefr. (Corporal) Bernh. Klassen, Uffz. (Sergeant) Albert Mann, Schtz. (Private) Fritz Wagner and Uffz. (Sergeant) Albert Zimmer.

In the course of seven decades, only two pictures fell out of the album. One is missing. The other — a group picture of 11 officers — is loose, allowing a faintly penciled-in caption to be read, placing it in Bregenz, Austria, on Jan. 1, 1942.

This group portrait was printed on a much different paper. It is the only loose picture in the album with a caption.

Private collection, via The New York Times

The concluding part of the album is centered in Bavaria, first at the Gebirgs-Motor-Sportschule (Mountain Motorsports School) in the town of Kochel am See, operated by the National Socialist Motor Corps. Then it moves to Munich, where the photographer dresses in civilian clothes and seems to have a female companion at his side — or in his viewfinder — at all times. “She’s doing her best to look like Marlene Dietrich,” noted Prof. Marvin J. Taylor, the director of the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University, as he looked at a particularly fetching pose.

Private collection,

via The New York TimesPage 24: Outside the Bavarian State Opera in Munich.

Professor Taylor called attention to the fact that the pictures were printed on two different types of paper: Agfa Brovira and Leonar. He invited us to consider the possibility that the pictures were culled from a number of sources, not just the PK photographer’s own work; that the album may have been compiled and pasted up by his companion or someone else with little interest in faithful narrative cohesion or chronological order.

Beware of inference, in other words. Professor Taylor has learned this lesson from dealing with other personal photo albums. “We think we can get so close to these people, but we can’t,” Professor Taylor said. “They are not the same people we are. We come up with assumptions — and the material always undermines what we think.”

Dr. Uziel agreed. “The eclectic selection of topics, the different styles of photography and the different papers may suggest an album fetched together by someone else,” he said.

At the very least, Professor Wolff said, there are two albums contained between the covers: one showing the Eastern Front and the other showing Munich and Bavaria. “Maybe the key,” he said, “is to fit them together.” We welcome your assistance in trying to do so.

Locations, Known and Unknown

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 4: What is this mural doing in Prussia? Is this even in Prussia?

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 4: This building has a Nazi emblem at the cornice.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 5: The Opera and Ballet Theater in Minsk.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 6: Presumably Minsk.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 12: The Malbork Castle in Malbork, Poland (known in German as Marienburg). The tower was destroyed in 1945.

Private collection, via The New York TimesPage 18: Presumably at the Mountain Motorsports School.

William P. O’Donnell, assistant editor and manager of image support, made all but two of the scans. Reporting was contributed by J. P. Roth.

Fonte

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento