Un popolo, la foresta pluviale e

la lotta per la sopravvivenza

Fotografie di James Withlow Delano

7-23 ottobre 2011, Fotoleggendo - ISA, Via del Commercio 13 – Roma

7-23 ottobre 2011, Fotoleggendo - ISA, Via del Commercio 13 – Roma

La mostra resterà aperta fino al 23 ottobre. Circa quaranta fotografie in bianco e nero di James Withlow Delano per un’indagine sul carburante bio-diesel e su un particolare tipo di produzione, quella che si ottiene dalla coltivazione di una palma prodotta soprattutto in Malesia, secondo produttore al mondo. Il 20 dicembre 2006, l’Assemblea Generale delle Nazioni Unite ha adottato una risoluzione proclamando il 2011 Anno Internazionale delle Foreste per sostenere l’impegno di favorire la gestione, la conservazione e lo sviluppo sostenibile delle foreste di tutto il mondo. La produzione di biodisel è un nuovo mercato che si sta orientando in due direzioni: quella sostenibile, in cui vengono utilizzati i rifiuti e gli scarti agricoli e, dall’altro lato, il biodisel prodotto dalla palma. Questa seconda modalità di produzione, gestita dalle multinazionali, ha avviato uno sfruttamento indiscriminato del territorio usato ormai quasi esclusivamente come terreno per la piantagione delle palme da cui ricavare il bio-carburante. Così la Foresta Pluviale della Malesia sta progressivamente scomparendo e la popolazione indigena (i "little people") sta perdendo velocemente la propria terra, la propria casa e la propria vita.

Le straordinarie fotografie di Delano ci raccontano la storia di queste terre martoriate da una modalità di produzione sconsiderata, che sta devastando una popolazione indifesa e un territorio che è una grande risorsa per l’umanità. La Foresta Pluviale con i suoi 130 milioni di anni, con un patrimonio di piante medicinali ancora sconosciute e che potrebbero offrire nuove cure persino per i tumori, con le sue 200 specie di animali terrestri, tra cui l'homo sapiens, e oltre 300 specie di uccelli, e 14.500 specie di piante fiorite e alberi, rappresenta un tesoro da proteggere. Invece si sta progressivamente trasformando in un deserto "verde", caratterizzato ormai da una specie arborea esotica (palma da olio africana), tanta erba, alcune felci e quasi nessun terriccio e, soprattutto, in una risorsa economica per i soliti investitori senza scrupoli.

“A coloro che sostengono il fervido appello del carburante bio-fuel come l’alternativa ecologica al petrolio, io dimostro il contrario. Il bio-fuel non è né ecologico, né alternativo, soprattutto in Malesia. Due popolazioni indigene - piccole in statura, in numero e piccole agli occhi del governo – stanno perdendo o hanno già perso la foresta pluviale, a causa del disboscamento e definitivamente per la piantagione della palma da olio. La Malesia è il secondo produttore al mondo di questa pianta dopo l’Indonesia, vicina di dimensioni maggiori. Questa statistica impressionante è stata raggiunta a causa del sacrificio involontario delle minoranze etniche.”James Whitlow Delano

Le fotografie della mostra saranno vendute all’asta per sostenere il progetto benefico di Sport senza Frontiere Onlus per favorire l’integrazione sociale e il diritto allo sport di bambini e ragazzi in difficoltà, discriminati. Il progetto si propone di offrire loro attività sportiva gratuita. Fonte

Sam (l) and Dolah (r), Batek Negrito men, are overshadowed by towering primary rainforest crowding a muddy logging road in the core of their homeland just outside Taman Negara National Park. The road gives loggers access to giant trees of this virgin forest, which they will cut down for profit. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

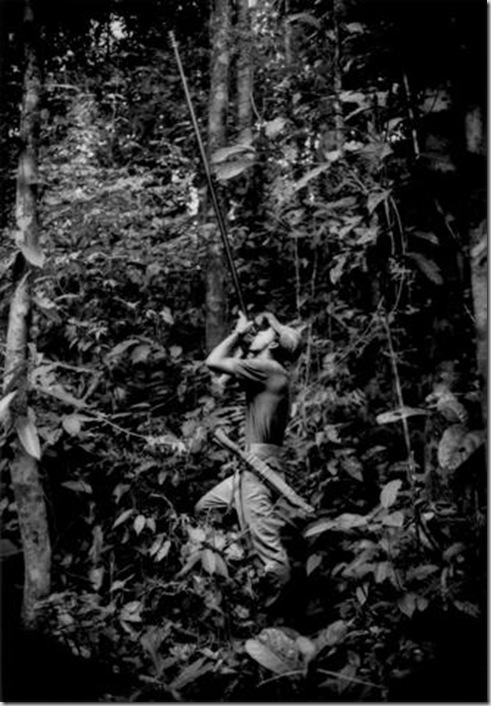

Adonia, a young Penan hunter, takes a shot at a small bird with his blowpipe in the primary Borneo rainforest that surrounds Long Benali, Sarawak, Malaysia. Darts are made from palm fronds; the pith of the forest palm is used to create an airtight seal with the blowpipe. Poison, made from the latex of a "Tajem" (Ipoh) tree, is applied to the dart. The poison interferes with the functions of the heart, causing a lethal arrhythmia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Adonia, a young Penan hunter, takes a shot at a small bird with his blowpipe in the primary Borneo rainforest that surrounds Long Benali, Sarawak, Malaysia. Darts are made from palm fronds; the pith of the forest palm is used to create an airtight seal with the blowpipe. Poison, made from the latex of a "Tajem" (Ipoh) tree, is applied to the dart. The poison interferes with the functions of the heart, causing a lethal arrhythmia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. Palms in the undercanopy of the rainforest in Taman Negara National Park, 434,300 hectares (1,676 sq. miles) of protected primary rainforest that supports tigers, Sumatran rhinoceros, Asian elephants, Malaysian gaur (wild bovine), tapir, gibbons, and monkeys, totalling over 200 species of terrestrial animals, over 300 species of birds and over 1,000 species of butterfly. Malaysia's dwindling rainforests are home to over 14,500 species of flowering plants and trees. This is the homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Palms in the undercanopy of the rainforest in Taman Negara National Park, 434,300 hectares (1,676 sq. miles) of protected primary rainforest that supports tigers, Sumatran rhinoceros, Asian elephants, Malaysian gaur (wild bovine), tapir, gibbons, and monkeys, totalling over 200 species of terrestrial animals, over 300 species of birds and over 1,000 species of butterfly. Malaysia's dwindling rainforests are home to over 14,500 species of flowering plants and trees. This is the homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. A rapid transition from old growth rainforest (l), the most diverse ecosystem on earth, to a palm oil plantation (r), a great green desert. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

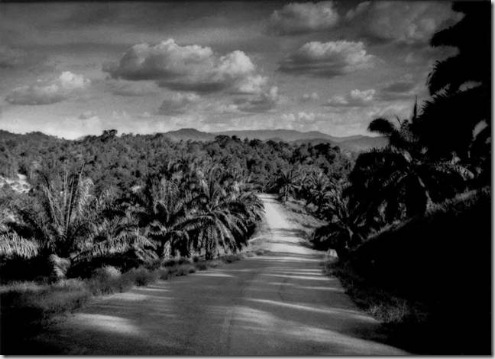

A rapid transition from old growth rainforest (l), the most diverse ecosystem on earth, to a palm oil plantation (r), a great green desert. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. A muddy logging road in the heart of the Batek Negrito homeland that has been surveyed and marked for logging. This is the last, very narrow strip of old growth rainforest that still exists between Taman Negara National Park and massive oil palm plantations. Less than a generation ago, these plantations were also old growth rainforest and the homeland of the Batek. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

A muddy logging road in the heart of the Batek Negrito homeland that has been surveyed and marked for logging. This is the last, very narrow strip of old growth rainforest that still exists between Taman Negara National Park and massive oil palm plantations. Less than a generation ago, these plantations were also old growth rainforest and the homeland of the Batek. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. Logging trucks (l) on the longest paved road into the interior of the Borneo rainforest. In Sarawak, there are thousands of muddy logging roads probing into every valley and canyon. The paved road (r) to the giant Bakun Hydroelectric Dam, Sarawak, Malaysia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

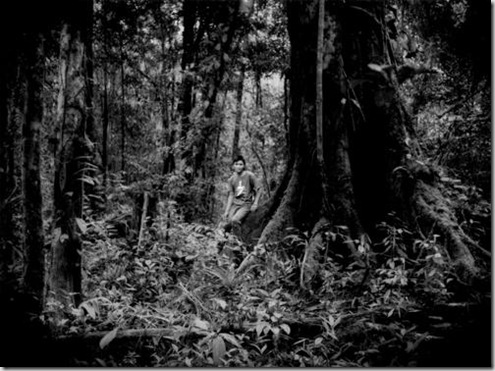

Logging trucks (l) on the longest paved road into the interior of the Borneo rainforest. In Sarawak, there are thousands of muddy logging roads probing into every valley and canyon. The paved road (r) to the giant Bakun Hydroelectric Dam, Sarawak, Malaysia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011. Young Penan man leans against giant forest tree in virgin forest that Samling Global Ltd., a logging company, has a concession to log. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kepang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Young Penan man leans against giant forest tree in virgin forest that Samling Global Ltd., a logging company, has a concession to log. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kepang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Penan men, Dennis (l) and Adonia (r), walk down a logging road, one of a network of roads used by Shin Yang Group to "selectively" log six months earlier. Bulldozers ripped straight up the mountain to cut down the biggest rainforest trees as quickly as possible. Now they have left behind a wounded forest. This had been a productive hunting ground for the Penan, but the numbers of wild animals, such as wild boars, monkeys, deer, hornbills, have dropped precipitously. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Clear cutting Borneo's rainforest (bottom half of photograph) for conversion to oil palm plantations (top right quarter of frame) seen from the air. Oil palm plantations are impoverished "green deserts". Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove of Princeton University, analyzing data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, found that 55 to 59 percent of oil palm expansion in Malaysia came at the expense of the rainforest. Between 1990 and 2005 the area of oil palm plantations in Malaysia more than doubled to 3.6 million hectares (13,900 sq. miles) while Malaysia correspondingly lost roughly 1.5 million hectares (5,791 sq. miles) of forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Clear cutting Borneo's rainforest (bottom half of photograph) for conversion to oil palm plantations (top right quarter of frame) seen from the air. Oil palm plantations are impoverished "green deserts". Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove of Princeton University, analyzing data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, found that 55 to 59 percent of oil palm expansion in Malaysia came at the expense of the rainforest. Between 1990 and 2005 the area of oil palm plantations in Malaysia more than doubled to 3.6 million hectares (13,900 sq. miles) while Malaysia correspondingly lost roughly 1.5 million hectares (5,791 sq. miles) of forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011. Palm oil processing plant where the rainforest once stood and where the Batek Negritos lived, north of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia. The rainforest must be clear cut before oil palm can be planted. Oil palm plantations are impoverished "green deserts." Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Palm oil processing plant where the rainforest once stood and where the Batek Negritos lived, north of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia. The rainforest must be clear cut before oil palm can be planted. Oil palm plantations are impoverished "green deserts." Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. The productive lifespan for oil palm trees is 20 to 25 years. "Senile" trees are cut down and replaced with younger more productive trees that can yield over 20 tons per hectare/year. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kelantan State, Peninsular Malaysia, 2011.

The productive lifespan for oil palm trees is 20 to 25 years. "Senile" trees are cut down and replaced with younger more productive trees that can yield over 20 tons per hectare/year. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kelantan State, Peninsular Malaysia, 2011. Kelabit man holds the skull of a helmeted hornbill, an endangered species, delivered to his house freshly killed by a Penan hunter. The birds are valued for hornbill ivory found in their thick bill and for their long tail feathers, which are used as decoration for Dayak people's ceremonial headwear. Despite posters distributed by the Malaysian government with illustrations of protected animals and the fines for killing them, any animal still seems to be fair game to local hunters. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Lellang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Kelabit man holds the skull of a helmeted hornbill, an endangered species, delivered to his house freshly killed by a Penan hunter. The birds are valued for hornbill ivory found in their thick bill and for their long tail feathers, which are used as decoration for Dayak people's ceremonial headwear. Despite posters distributed by the Malaysian government with illustrations of protected animals and the fines for killing them, any animal still seems to be fair game to local hunters. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Lellang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011. Batek Negrito women rest beside a muddy logging road in the heart of the Batek Negrito homeland that has been surveyed and marked for logging. This last, very narrow strip of old growth rainforest is sandwiched between Taman Negara National Park and massive oil palm plantations that less than a generation ago were old growth rainforest. The woman in the foreground on the left is wearing waxy leaves in her hair for decoration. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Batek Negrito women rest beside a muddy logging road in the heart of the Batek Negrito homeland that has been surveyed and marked for logging. This last, very narrow strip of old growth rainforest is sandwiched between Taman Negara National Park and massive oil palm plantations that less than a generation ago were old growth rainforest. The woman in the foreground on the left is wearing waxy leaves in her hair for decoration. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.  An elder Penan woman is splitting rattan collected from the Borneo rainforest for use in weaving and binding. Rattan, which is a climbing palm tree, grows well only in the primary rainforest. Long Kepang lies deep in the rainforest and is only accessible by foot. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kepang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

An elder Penan woman is splitting rattan collected from the Borneo rainforest for use in weaving and binding. Rattan, which is a climbing palm tree, grows well only in the primary rainforest. Long Kepang lies deep in the rainforest and is only accessible by foot. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kepang, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.  Workers harvesting the fruit from oil palms, much of which will be refined into "green" biofuel. These workers are ethnic Malay, though perhaps the majority of workers on oil palm plantations are ethnic Tamils (Southern Indians who came to Malaysia during the British colonial era). A few Batek Negrito men earn money as unskilleded day laborers on oil palm plantations. Image by James Whitlow Delano, North of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Workers harvesting the fruit from oil palms, much of which will be refined into "green" biofuel. These workers are ethnic Malay, though perhaps the majority of workers on oil palm plantations are ethnic Tamils (Southern Indians who came to Malaysia during the British colonial era). A few Batek Negrito men earn money as unskilleded day laborers on oil palm plantations. Image by James Whitlow Delano, North of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. Young female Batek Negrito students all wear "hijab" Muslim headscarves on the campus of the regional boarding school built by the Malaysian government specifically for the Batek at Post Lebir. The Malay teaching staff claim that the girls have chosen to wear the hijab because they have converted to Islam from the indigenous Batek animimism. Batek residents in Post Lebir dispute this claim. There is a high drop-out rate among the Batek in part because long separations from families in a culture that lacks motor transportation are especially difficult. Children are particularly ill-prepared for coping with long separations. Near Manek Urai, Kelantan, Malaysia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Young female Batek Negrito students all wear "hijab" Muslim headscarves on the campus of the regional boarding school built by the Malaysian government specifically for the Batek at Post Lebir. The Malay teaching staff claim that the girls have chosen to wear the hijab because they have converted to Islam from the indigenous Batek animimism. Batek residents in Post Lebir dispute this claim. There is a high drop-out rate among the Batek in part because long separations from families in a culture that lacks motor transportation are especially difficult. Children are particularly ill-prepared for coping with long separations. Near Manek Urai, Kelantan, Malaysia. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. Workers, mostly Indonesians of dubious visa status, cut logs into planks of lumber for export in one of the sawmills that line the banks of Batang (River) Kemena, Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia. According to the United Nations Environment Program - World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Malaysia lost an average of 78,500 hectares (303 sq. miles) of forest per year between 1990 and 2000. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Workers, mostly Indonesians of dubious visa status, cut logs into planks of lumber for export in one of the sawmills that line the banks of Batang (River) Kemena, Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia. According to the United Nations Environment Program - World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Malaysia lost an average of 78,500 hectares (303 sq. miles) of forest per year between 1990 and 2000. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011. A logging camp in northern Peninsular Malaysia on the edge of the homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Manik Urai, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

A logging camp in northern Peninsular Malaysia on the edge of the homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Manik Urai, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.  Oil palm plantations stretching to the horizon and to the Borneo coast seen from the air near Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia. Once the rainforest has been logged out, conversion to oil palm plantations, a source of biofuel, often follows. Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove of Princeton University, analyzing data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, found that 55 to 59 percent of oil palm expansion in Malaysia came at the expense of the rainforest. Between 1990 and 2005 the area of oil palm plantations in Malaysia more than doubled to 3.6 million hectares (13,900 sq. miles) while Malaysia correspondingly lost roughly 1.5 million hectares (5,791 sq. miles) of forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Oil palm plantations stretching to the horizon and to the Borneo coast seen from the air near Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia. Once the rainforest has been logged out, conversion to oil palm plantations, a source of biofuel, often follows. Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove of Princeton University, analyzing data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, found that 55 to 59 percent of oil palm expansion in Malaysia came at the expense of the rainforest. Between 1990 and 2005 the area of oil palm plantations in Malaysia more than doubled to 3.6 million hectares (13,900 sq. miles) while Malaysia correspondingly lost roughly 1.5 million hectares (5,791 sq. miles) of forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Fruit harvested from oil palm trees piled on the back of a truck in the former homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Near Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Security sign at the entrance to the seafront estate of the owner of Shin Yang Group leaves little doubt what would happen to an intruder. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Luak Bay, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

A newly planted field of oil palms in an area of vast oil palm plantations. Less than a generation ago this was the rainforest homeland of the Batek Negrito people. Image by James Whitlow Delano, North of Taman Negara National Park, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Batek Negrito man hitches a ride on the back of a motor bike along a dusty highway that runs through vast oil palm plantations. This area used to be the hunting and gathering grounds of the Batek. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

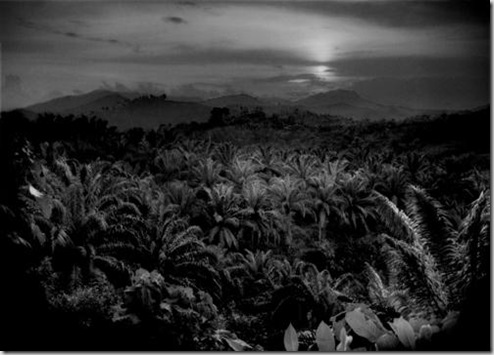

A view of where the vast oil palm plantations abut the rainforest-covered mountains of Taman Negara National Park. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Near Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

A logging road rips straight up a steep slope; heavy rains will make certain this scar in the earth will remain. The Penan of Long Benali have built barricades to keep loggers out, but in the end, loggers almost inevitably win. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Near Long Benali, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Young Batek Negrito man on a new logging road that cuts into the forest along the Taman Negara National Park boundary right up to the edge of the park next to Kuala Koh, Kelantan. The Batek Negritos use this road to get to a riverside settlement of semi-nomads on a tributary to the Lebir River. Almost all the land north of the park, their traditional homeland, has been clear cut and converted to oil palm cultivation. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Young Batek Negrito man on a new logging road that cuts into the forest along the Taman Negara National Park boundary right up to the edge of the park next to Kuala Koh, Kelantan. The Batek Negritos use this road to get to a riverside settlement of semi-nomads on a tributary to the Lebir River. Almost all the land north of the park, their traditional homeland, has been clear cut and converted to oil palm cultivation. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.  In his element: Balang Weng, a Penan man, scans the rainforest canopy where he heard a crashing sound made by an unseen macaque (monkey). The Penan used to roam the rainforest following game. Now, they can no longer sustain themselves from the forest alone and supplement their diet with rice bought from the nearest towns, like Long Lellang. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kelamu, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

In his element: Balang Weng, a Penan man, scans the rainforest canopy where he heard a crashing sound made by an unseen macaque (monkey). The Penan used to roam the rainforest following game. Now, they can no longer sustain themselves from the forest alone and supplement their diet with rice bought from the nearest towns, like Long Lellang. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Long Kelamu, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.  Last nail in the rainforest's coffin: First the rainforest is "selectively" logged once or even several times, then clear-cut, then oil palm is planted on the bare ground. Finally a major road is cut, clearly demarcating the land for permanent development. Batek Negritos used to live in the forest that covered this land. Image by James Whitlow Delano, North of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

Last nail in the rainforest's coffin: First the rainforest is "selectively" logged once or even several times, then clear-cut, then oil palm is planted on the bare ground. Finally a major road is cut, clearly demarcating the land for permanent development. Batek Negritos used to live in the forest that covered this land. Image by James Whitlow Delano, North of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. The wary-eyed, almost elfin beauty of a mother holding her newborn child in the 130 million-year-old rainforest where he was born. The Batek Negritos, like many forest dwelling people, can be quite aloof in the presence of strangers from outside the forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011.

The wary-eyed, almost elfin beauty of a mother holding her newborn child in the 130 million-year-old rainforest where he was born. The Batek Negritos, like many forest dwelling people, can be quite aloof in the presence of strangers from outside the forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2011. Penan clan from Long Kelamu build a barricade to block loggers from Samling Global Ltd. from accessing one of the last tracts of virgin forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.

Penan clan from Long Kelamu build a barricade to block loggers from Samling Global Ltd. from accessing one of the last tracts of virgin forest. Image by James Whitlow Delano, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2011.All images © James Whitlow Delano

james whitlow delano

jameswhitlowdelano.photoshelter

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento