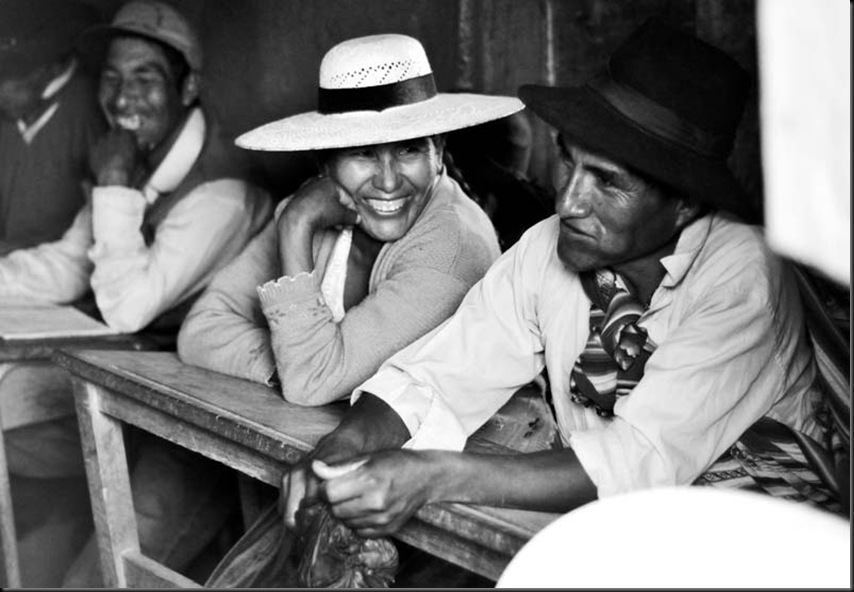

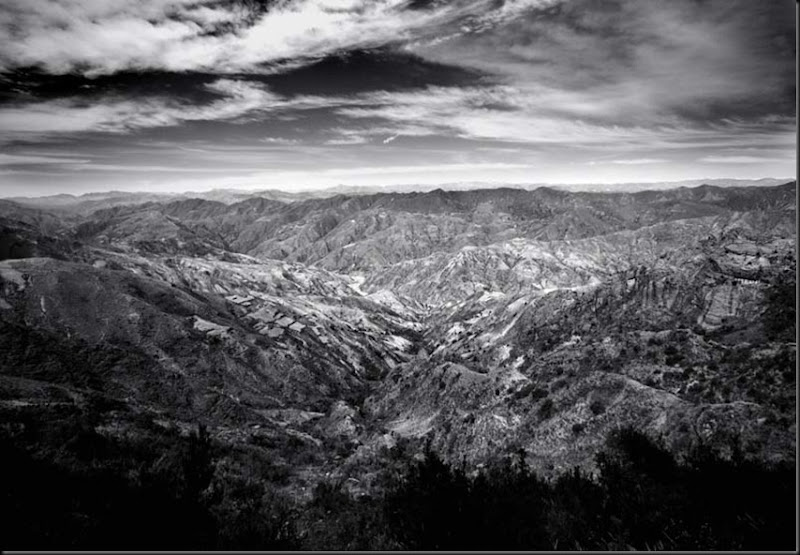

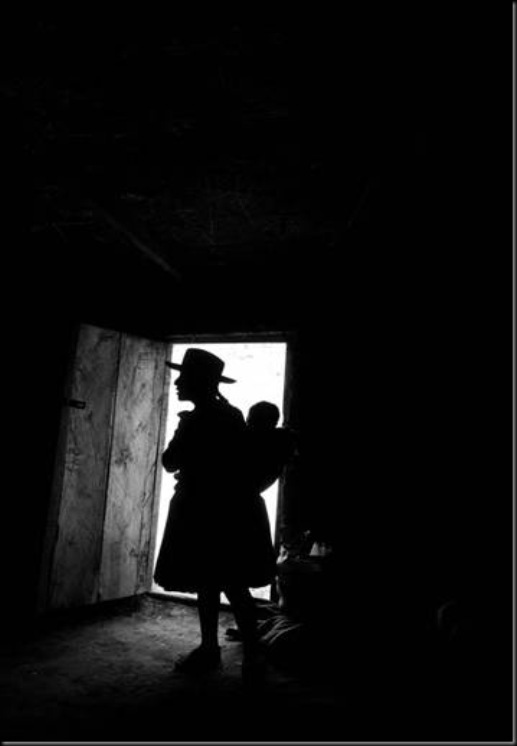

Durante años, el fotógrafo suizo Jean-Claude Wicky penetró en las

profundidades de las minas de Bolivia, enterrándose con los trabajadores en los

laberintos de Colquiri, Viloco, Huanuni y Potosí, "donde los hombres se

enfrentan con la roca y dialogan con el diablo".

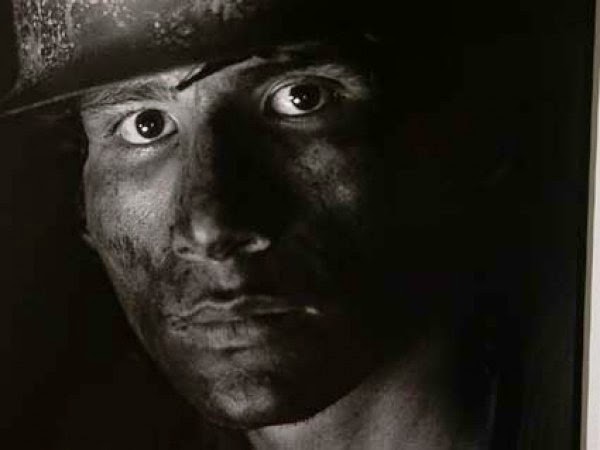

"En las profundidades de las montañas bolivianas descubrí,

fascinado, un diablo de arcilla llamado Tío. Es el dueño del mineral y de las

vetas, que puede esconder o revelar. Este príncipe de las tinieblas tiene el

poder de decidir el destino de los que invaden su territorio para apropiarse de

sus riquezas. Cuando se ofende, el Tío es capaz de aplicar los castigos más

terribles. Por ello, los mineros lo honran con ceremonias semanales llamadas

ch'alla. Le solicitan su protección y ayuda a cambio de hojas de coca, alcohol

y cigarrillos"

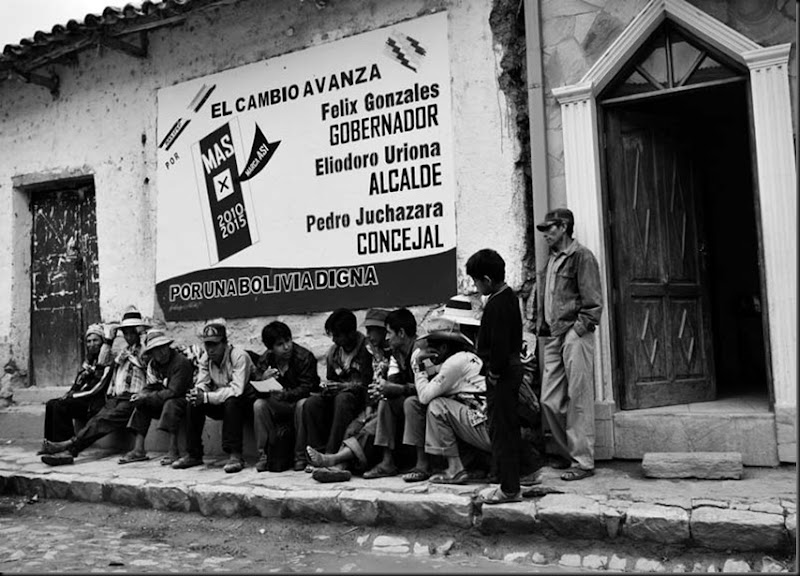

Between 1984 and 2001, Jean-Claude Wicky, a Swiss documentary

photographer, took more than 80 photos at 30 mining centres in Bolivia.

His pitch-black pits, faces contorted by rubble, figures teetering over perilous cliff-tops and views down shudderingly steep shafts have toured to 12 Latin American countries and 36 cities, seen by more than half a million people.

Arriving at Geevor, the tin mine which spent most of the 20th century shifting thousands of tons of black tin, they serve as a rare atmospheric parallel between Cornwall and South America.

"The similarities between the miners of Bolivia today and those of Cornwall generations ago is remarkable," says Bill Lakin, the Chair of Trustees at the mine.

"I was astonished by Jean Claude's haunting photography. No-one can fail to be moved by this stunning exhibition."

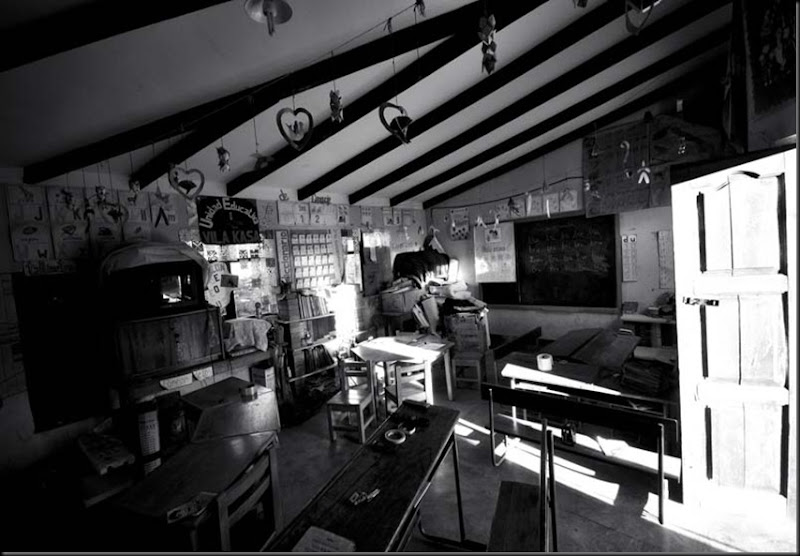

For his part, Wicky underlines the lack of health and safety the miners – ranging from children to pensioners – face in a working environment which is stiflingly hot and full of danger.

"This piece of work is my song of friendship to the people of Bolivia and all those whose daily work consists of seeking their destiny in the depths of the earth," he says.

Jean-Claude Wicky is a Swiss documentary photographer. From 1969 to 1975 he travels around the world and makes his debuts in photography in a 22-months stay in Japan.

He lives in Moutier, Switzerland where he has his studio, but photographs mostly in South America and South East Asia.

In the 80's he gets twice the Federal grant, a grant from the State of Berne and the cultural prize of the town of Moutier.

In 1984 he begins a photo project on the Bolivian miners and visits Bolivia on a regular basis for 17 years while exploring some 30 mining centres throughout the country. This photographic work ends with the exhibition «Bolivian miners» and later the book «Bolivianminers». The exhibition was shown in 12 Latin American countries, 36 cities and was visited by over 500.000 people. It is currently in Mexico.

His work has been published in numerous magazine and newspapers including Geo Magazine and Smithsonian Magazine.

He has exhibited photographs in museums and galleries throughout Europe and Latin America. touslesjourslanuit

His pitch-black pits, faces contorted by rubble, figures teetering over perilous cliff-tops and views down shudderingly steep shafts have toured to 12 Latin American countries and 36 cities, seen by more than half a million people.

Arriving at Geevor, the tin mine which spent most of the 20th century shifting thousands of tons of black tin, they serve as a rare atmospheric parallel between Cornwall and South America.

"The similarities between the miners of Bolivia today and those of Cornwall generations ago is remarkable," says Bill Lakin, the Chair of Trustees at the mine.

"I was astonished by Jean Claude's haunting photography. No-one can fail to be moved by this stunning exhibition."

For his part, Wicky underlines the lack of health and safety the miners – ranging from children to pensioners – face in a working environment which is stiflingly hot and full of danger.

"This piece of work is my song of friendship to the people of Bolivia and all those whose daily work consists of seeking their destiny in the depths of the earth," he says.

-----------------------------------------------------

Jean-Claude Wicky is a Swiss documentary photographer. From 1969 to 1975 he travels around the world and makes his debuts in photography in a 22-months stay in Japan.

He lives in Moutier, Switzerland where he has his studio, but photographs mostly in South America and South East Asia.

In the 80's he gets twice the Federal grant, a grant from the State of Berne and the cultural prize of the town of Moutier.

In 1984 he begins a photo project on the Bolivian miners and visits Bolivia on a regular basis for 17 years while exploring some 30 mining centres throughout the country. This photographic work ends with the exhibition «Bolivian miners» and later the book «Bolivianminers». The exhibition was shown in 12 Latin American countries, 36 cities and was visited by over 500.000 people. It is currently in Mexico.

His work has been published in numerous magazine and newspapers including Geo Magazine and Smithsonian Magazine.

He has exhibited photographs in museums and galleries throughout Europe and Latin America. touslesjourslanuit

All images © Jean-Claude Wicky

.jpg)