In Africa and its diaspora the mask transforms mortals

into gods and makes a political point.

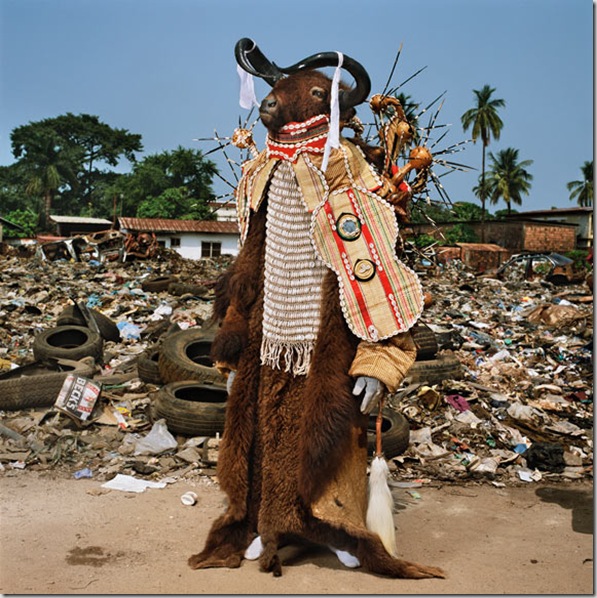

SIERRA LEONE

SIERRA LEONEOn festival days in Freetown, social clubs parade in the streets, led by an ancestral “devil.” This fierce and fancy water buffalo spirit is the figurehead for a men’s group.

HAITI

HAITINot all masquerades require masks, or occur in Africa. In the Haitian port city of Jacmel three boys become Pa Wowo—painted, coconut-leaf-skirted peasants who personify poverty—for the spring carnival. When children participate, says art historian Jean Borgatti, “everyone loves it, because it means continuity.”

BURKINA FASO

BURKINA FASOAn elephant and a bat pose at the Dodo Masquerade in Burkina Faso, an event where children don masks, sing, and dance under a full moon.

GHANA

GHANAIn the town of Winneba a cowboy is both protector and fashion plate. This one, from the year-end, century-old Fancy Dress Festival, wears a playful mix: bright holiday ornaments, zebra-striped cloth that conjures wildlife, and imported textiles that evoke African, European, and popular cultures.

BENIN

BENINThis strange character, which appears at a yearly sacred festival in Agonli honoring women, is known as You Can’t Buy Wisdom at the Market. The mishmash garb may satirically make the point that enlightenment is never for sale, says scholar Babatunde Lawal—a message that is part of the sacred event.

ZAMBIA

ZAMBIA“Wearing a mask made of twigs, cardboard, and beeswax, this youth—part of a coming-of-age ceremony—is dressed as one of the ancestral characters known as Likishi,” says photographer Phyllis Galembo.

SIERRA LEONE

SIERRA LEONEMathom (Limba Devil) and Ghongorli, part of the National Dance Troupe, in Freetown, Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE

SIERRA LEONEFrills and ruffles lend a feminine air to this dancing joker, called a jollay, in a Fullahtown parade. Despite the girlish garb, the actor is a man. Like Greek theater, African masquerades reflect male-dominated societies. Women are often excluded because masks are said to link the wearer to a dangerous spirit world. “Just putting one on,” says Borgatti, “is a charged event.”

SIERRA LEONE

SIERRA LEONENew materials and influences push artists to improvise. In Kroo Bay a hunting society’s deer spirit flaunts a traditional carved-wood mask, store-bought gloves, and armor made of gourd slices sewn to a net. One scholar thinks the artist may have been inspired by chain mail seen in a Hollywood movie.

NIGERIA

NIGERIA“I took this photograph when I was visiting the Cross River village of Nkim,” says Galembo. “There was no masquerade going on at the time. But carved-wood, animal-skinned Janus masks like this one appear at funerals, ceremonies honoring Nigerian kings and chiefs, and other rituals. The feathers are a symbol of power. Masks depicting two faces—one of which is usually gentle, the other fierce—appear in many different cultures.”

NIGERIA

NIGERIADuring Christmastime in urban Calabar some spirits are portrayed with forest greenery and netlike fabrics

NIGERIA

NIGERIAOther spirits represent nature or esteemed ancestors who guide, judge, or entertain the living.

NIGERIA

NIGERIAIn the village of Alok a carving of the female water spirit Mami Wata crowns a costumed man’s headdress. Mami Wata is controversial—linked to health and wealth in Africa and its diaspora, demonized by some Muslim and Christian fundamentalists.

NIGERIA

NIGERIAThe diverse Cross River region is home to a host of masquerade traditions. In remote Eshinjok an acrobatic troupe dazzles eyes and ears with vibrantly dyed, hand-looped fibers and ankles bearing shells, bells, and bottle caps.

HAITI

HAITIMan with whip in Jacmel, Haiti

HAITI

HAITIThe tools of modern revolutions, a gun and a phone, are held by a masked youth. Other parts of his hellish carnival attire connect to Haiti’s past. To symbolize the suffering of slaves, he’s wrapped in a rope, his skin glazed in charcoal and molasses—an inexpensive, easy-to-make masquerade worn since colonial times.

www.galembo.com

Fonte

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento