La Belle Epoque's Beauty

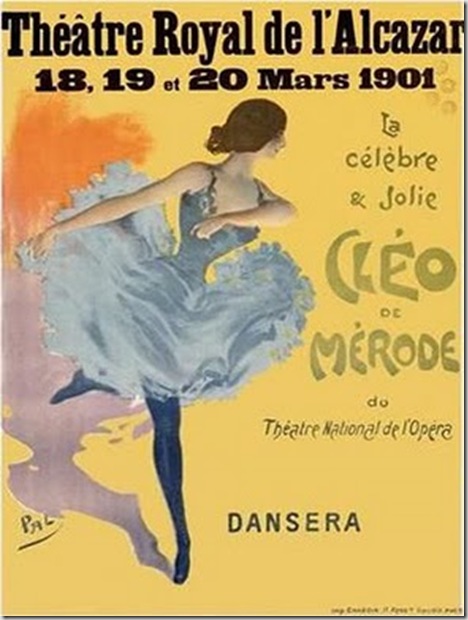

Cléo de Mérode (1875-1966), an international sensation, one of the the most photographed woman in the world in her time, was a French ballerina, who achieved fame with her face, not her feet.

Born in Paris, Cléopatra Diane de Mérode belonged to a Belgian noble family of some means; her father, Karl von Merode, was a landscape painter. She started studying dance at 7 and made her professional debut at age eleven. Cleo entered the Paris Opéra ballet at the times when female performers were assumed to be courtesans. The Opéra corps de ballet had a reputation as a "'national harem" (Lenard R. Berlanstein), it was a subject of "a thousand salacious anecdotes, a thousand scandalous rumors."

Cléo was a good dancer but above all her beauty caught the public's eye - by 13, she already had posed for Jean-Louis Forain and Edgar Degas, who often sketched her.

Alexandre Falguière sculpted The Dancer in her image (Musée d'Orsay). In 1895, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec did her portrait, as would Charles Puyo and Alfredo Muller.

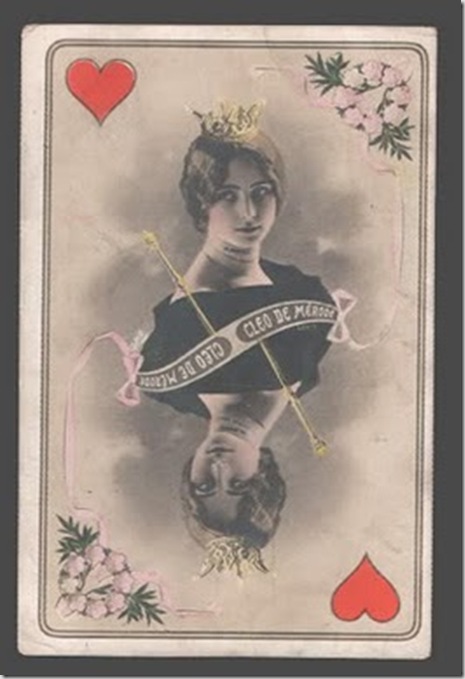

At sixteen she debuted her trend-setting, hallmark hairstyle: over the ears, usually in a chignon, often worn with metal bands.

In 1896 mademoiselle de Merode was elected "reine de beaute" by L'Illustration.

In 1895 in Paris the stiff-looking elderly king King Leopold II of Belgium had made the acquaintance of this lovely woman. She was 40 years younger than the king, and within the Tout Paris he was known as 'Cleopolde'. The king's alleged liason with Cleo filled the gossip columns of Europe.

In her memoirs Le Ballet de ma vie (1955) she denies that she had been a courtesan. This had little effect on public opinion though..

Cleo successfully sued feminist Simone De Beauvoir in 1955 for wrongly describing Cleo in public as a prostitute who had taken an aristocratic-sounding stage name as self-promotion. Cleo's defence was that she was a professional dancer and member of the old, noble, and distinguished de Merode family.

De Merode got 1 franc damages in suit against Simone de Beauvoir.

Cleo lived with her overprotective mother until the latter's death in 1899 (Cléo was almost 24) and had just two romantic involvements, both of them discreet and long-term.

She was never conscious of her beauty, though crowds followed her when she went out shopping, and when she danced with Rupert Doone who looked like nothing off stage, but had a great talent for stage makeup (which she had not), Cleo said, "He is much prettier than me!" (Merode was the first woman to dance with a male partner in the Russian Ballet)

Cleo continued to dance until her early fifties and was very popular in her in her ancestral homeland of Austria where she befriended the artist Gustav Klimt. She retired to Biarritz and died in 1966 at age 91 and is entombed at Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

~~~

Arthur Symons (1865-1945), the British poet and critic, wrote:

'The men, if they have good figures, look well; they at least have the chance of looking well. But the women! Rare, indeed, is the woman who can look pretty, in her toilette or herself, as she comes out of the sea, wraps herself in a sort of white night gown, and saggers up the beach, the water running down her legs... The lines of the body are lost or deformed; there is none of the suggestion of ordinary costume, only a grotesque and shapeless image, all in pits and protuberances'.

The exception seemed to be Cleo de Merode, the famous Parisian dancer and courtesan for whom, to a man, the group of writers and artists lay in wait for the hour of her bathing. Symons in particular was enchanted: 'And there was Cleo de Merode, with her slim, natural, and yet artificial elegance, her little, straight face, so virginal and yet so aware, under the Madonna-like placidity of those smooth coils of hair, drawn over the ears and curved along the forehead; it is Cleo de Merode, who, more than anyone else sums up Dieppe.' (During the later nineteenth century, Dieppe became popular with English artists as a beach resort. Prominent literary figures such as Arthur Symons loved to keep up with the latest fads of avant-garde France and the decayed aristocracy here.)

Cléo de Mérode by Manuel Benedito Vives (1875-1963), 1910

~~~

Mercedes and auto racing in the Belle Epoque, 1895-1915 By Robert Dick

Even a king joined the ranks of Mercedes owners: Leopolde of Belgium. ... It was reported that, in August 1901, in her apartment in the Avenue Louise, he met her and the stylist Fernand Charles. The trio talked about the coachwork of the king's latest Mercedes, whereupon Mlle de Merode proposed two amply upholstered leather armchairs as seats. The king liked the idea, especially when Charles added a tulip-shaped aluminum covering for the seats. Messieurs Rheims and Auscher from the panelworkers Jacques Rothschild & Fils were responsible for the hand-beated execution, which combined art nouveau, comfort and lightweght construction.

~~~

The American telephone journal, Volume 8, 1903

Poor telephone girls; they are never allowed to rest in peace for long. The Stockholm telephone authorities are finding fault now with the way in whiich they do their hair. It appears that of late the Swedish lassies who put you through to number you ask for - or otherwise - have adopted the mode of coiffure first initiated by the French dancer Cleo de Merode, in which the hair drawn over the ears. The subscribers have since found a falling off in the hearing powers of the operators, as the result of which complaints of inefficiency in the service have been made, and the girls ordered to change their style of hair-dressing. This they have refused to do, and there seems a prospect of another labor crisis in Stockholm. - London Electricity.

~~~

Rethinking dance history: A reader Edited By Alexandra Carter 2004

In the beginning of the 20th century, interviews were still quite a novelty in European newspapers, having appeared as a true media genre only during the late 19th century. In Sweden, as in many other countries, whenever there was a guest performance, including a dancer with an assumed 'star quality', reporters stood in line in order to conduct their interviews... The famous French ballerina Cleo (visiting Sweden in 1903 and 1904) readily answers many kinds of personal questions, which Isadora Duncan (visiting Sweden in 1906) refuses to do. She prefers to talk about her school in Germany, the importance of physical education, and about art. In this sense she reveals a clever marketing strategy, adapted to her professional persona. But de Merode, who seemingly adjusts to the reporters' expectations, express agency of a different kind. She allows the reporters to sit in during her meetings with the theatre direstor as well, and shows a very strong-willed and efficient business mind. She is a career woman who is clearly aware of how she can make use of the reporters' interest in her private person. Both de Merode and Duncan act on the 'rules' of the interview, albeit in different ways, and thereby transform a structure of assumed intimacy and unmasking into one that reveals the workings of clever, professional entrepreneurs.

Cleo de Merode Arrives

The French Dancer Comes on the Steamship Spree to Remain Six Weeks

She was Falguiere's Model for "La Danseuse," Which Set All Artistic Europe Talking - How She Won Her Present Prominence

Cleo de Merode, premiere ballet dancer of the Grand Opera in Paris, the admiration of the Parisian boulevardier, the prized model of sculptors, and the protegee of a King, is here. She arrived on the steamship Spree yesterday morning, accompanied by her mamma, Maurice Forbee, manager of the Folies-Bergere, her personal representative; one maid, nine trunks, and a dog. She will dance for six weeks at koster & Bial's, and then must return to Paris.

Cleo de Merode sprang into notoriety about three years ago. She had before that been known as a graceful dancer with a pretty face in the ballet. But there are many such at the Grand Opera House; so she was simply classed with the 'many'. King Leopold of Belgium was attracted by her demure artlessness at that time, and made no secret of it. Straghtway she became an objest of curiosity which two other events intensified. The first of these was the winning of the "prize" at a beauty show, wherein she defeated Sibyl Sanderson and other equally famous beauties, and the second was the exhibition of Falguiere's statue of "La Danseuse" at the Salon. Mlle. de Merode was the model for it, and it made her the most talked of woman on the Continent.

The real name of the dancer is said to be Hortense Gervais, and it is added that she is the daughter of an humble family in Paris. This she denies, and she claims descent from the noble family of de Merode. She is twenty-three years of age and has been in the ballet of the Grand Opera for eight years, first as an humble coryphee. During this time she has danced but once away from the city and that was last summer, when she led at the first production of the ballet of "Phryne", by Louis Grant at Brussels.

In appearance Mlle. de Merode is about the medium height for a woman, slight in form, with masses of wavy brown hair arranged low on both side of her head. Her complexion is clear, and when she smiles her brown eyes light up and a little flush creeps up her cheeks. She has few of the mannerisms of her predecessors in vaudeville here. There was not one shrug of the shoulders at her reception yesterday afternoon, nor were her hands constantly in use as interpreters. She laughed in an embarrassed way at times, and would every once in a while drop her eyes to the floor.

"Yes," she said, "it was a delightful voyage, and I was ill but one day. All the rest of the time I was about the ship, playing the piano., pitching quoits, or talking with the many nice passengers. They were all so kind to me, and when I danced at the concert they were kind enough to applaud me much".

"When the steamer came up the bay this morning the hills and the forts and the beautiful houses on the shore made it charming. Then, too, the Statue of Liberty, is not that grand? But oh, your buildings are so high! I thought at first they might be the theatres and I was much frightened."

Of her dances she said: "There are four I will try here, the gavotte, the pavanne, a minuet of Louis XV and a dance of Louis XIII. In all of them my costums permits my wearing my hair this way, except in the minuet. There I wear a gray wig and (with a little laugh) you can see whether I have ears or not. You know somebody in Paris once said that the reason of my wearing my hair in this way was that I have the ears of a fawn. But I rode up and down the Bois with my hair high on my head to show them all it was untrue," and she tenderly patted her hair.

MERODE MYTH EXPOSED By Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph to The New York Times.

June 4, 1911, Sunday

LONDON, June 3, (by telegraph to Clifden, Ireland; thence by wireless.) -- In the recent chronique scandaleuse of royalty there is probably no more widely known story than that which linked the name of the late King Leopold of the Belgians with Cleo de Merode, the Parisian ballet dancer.

For years the monarch was punningly nicknamed Cleopold on account of his supposed association with Cleo, yet according to Xavier Paoli, the well-known Continental detective, whose special work connected with various royalties, the adventure with which Leopold II was credited for ten years in connection with Cleo de Merode must be relegated to the domain of pure fiction.

'I dare say," writes Paoli in The Contemporary Review for June," that it assited in advancing the young and attractive dancer quite as much as it annoyed the King.

"What gave rise to this absolutely gratuitous conviction on the part of public opinion was nothing more or less than a gossiping remark let fall behind the scenes at the Opera by some one who pretended he had met the King and the ballet dancer looking for a sequestered spot in the forest of Sarthe.

The scandal was hardy and tough. It ran for ten years without stopping to take breath. At the end of that period, which was long enough to turn any lie into truth, Leopold II one night at the opera asked a leading official to present Mlle de Merode to him, saying that he had never met the lady, although he 'had often heard of her'.

The leading official promptly adopted the view that the King was uncommonly deep, and yet it was true - he had never set eyes on Cleo in his life. The fact was proved by the candor of the words which he addressed to the dancer when she was brought up to be presented:

"Allow me to express all my regrets if the good fortune which people attribute to me has offended you at all. Alas! we no longer live in the days when a King's favor was not looked upon as compromising. Besides, I am only a little King."

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento