Throughout Nairobi, various grassroots initiatives led by young people have begun improving the quality of life for those living in the direst of conditions. Termed “youth groups” on the street, these initiatives could represent the future of long-term socioeconomic development in Kenya.

In January 2008, I photographed Kenya’s most violent conflict since independence. The pictures I made during the post-election violence exposed a nation frustrated with broken promises. Two years later, I returned with my cameras to see if these new promises, this time made in blood, would be kept. Instead, I found progress in the most unlikely of places.

In Kibera, where mounds of garbage grow between makeshift buildings and along paths and residences, the Usafi Youth Group has managed to develop a waste management system apart from the financial backing of any foreign NGO or their own government. Youth volunteers dig pit latrines to clear mounds of waste, opening up plots for sustainable agriculture projects on the newly fertilized earth. Other groups have created community toilets and bathhouses, and free education sessions on reproductive health and HIV/AIDS are organized and taught each week, all by youth leaders.

“We have to create something for ourselves so that life can move on,” Moses Amondi told me in response to the post-election violence. “And that’s why every day we wake up… we struggle with our hands, you know? If you tell people that in Kibera there is an agricultural farm, people cannot believe, because of the assumption they have. It’s our desire as young people to excel, and we’ll only excel if there is another helping hand that can come along.”

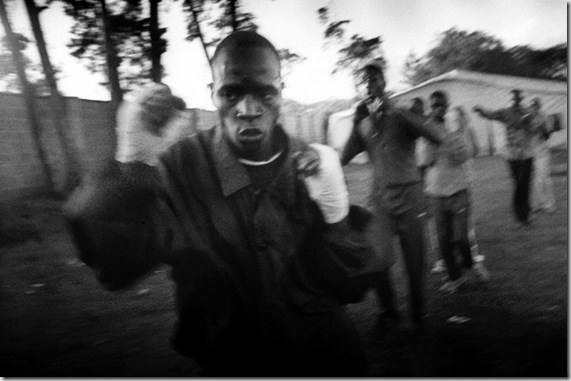

In some areas, athletic groups led by volunteer coaches have also begun to form, preventing idleness and crime among youth while encouraging a sense of pride in their own abilities. In the outskirts of Nairobi, volunteer boxing coach Hassan Abdul Kasalini prepared a team of youths for a bout. “Every generation has an obligation,” Kasalini told me. “We have an obligation for the other generations. We want to make a good name for ourselves. We don’t want people to think, Kibera – violence, violence, violence – all the time.”

But youth reform in Kenya is not without resistance. Power wielding politicians are well aware of the threat youth reformers pose to their political and economic strongholds. Consequently, most youth groups are purposefully independent of any affiliation to their own government. According to a study by Human Rights Watch, since 2002 “youths in some parts of the country [have] been offered money in exchange for their [voter] registrations cards,” and reports confirm that a large number of killings were carried out by youth of the lowest socioeconomic status. Indeed, systemic poverty is the greatest leverage politicians have over their own people.

“We were fighting for a change,” Kamau “Kelly” Nganga, age 21, told me. “We were voting for change, but it never happened, so we had to fight. I cannot see the change now. It can be worse in 2012, because the corruption we were fighting is still there, high up.”

In April of last year, United States ambassador Michael Ranneberger called on the young people of Kenya to seize active roles in the reform of their nation. The envoy, who had been moving around the country interacting with young people, said he sensed “a sea change of attitude” in the nation’s youth – that “the youth have woken up.” He went on to describe “a tidal wave below the surface” that “at one point is going to break” (Juma, 2010).

The goal of this project is to bring to light that movement. By documenting the work of Kenya’s youth reformers and the political and social challenges they face, this project will contribute to a balanced global perception of poverty and progress in Kenya by highlighting an immensely positive theme: that passionate, determined youth can incite change in its world. Through a photographic essay and an accompanying multimedia video, this project will aid youth reformers in the distribution of their message, while influencing the flow of financial support toward their initiatives.

A community leader addresses a crowd of predominantly Luo youth at a weekly Kamkunji meeting in the Kisumundogo village of Kibera. Kamkunji is the Swahili word for “small gathering,” and it provides a weekly venue for individuals to speak out about issues vital to the community. The gathering started in 1990 when Kenyans first fought for a multiparty government. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Youth of the Caribbean “Crew” rest as members wash vehicles for 100 Kenyan shillings. Caribbean Youth Reform gained its name after several violent youth in Kibera were “reformed” under the leadership of the organization’s founding members. Many youth groups began in 2008 as a result of the post-election violence which claimed the lives of over 1,000 Kenyans, and most operate with the goal of uniting the young people of conflicting tribes. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

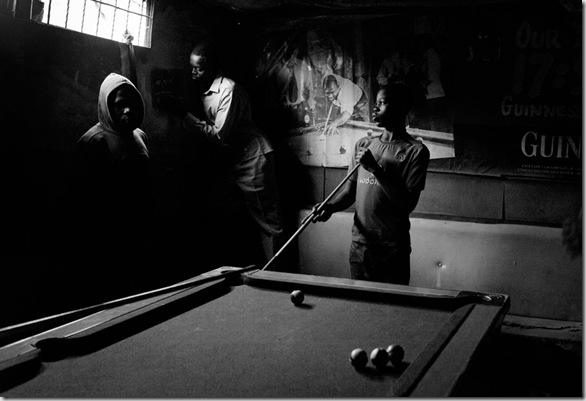

Youth play the popular billiards game “Whiteless” at the former Railbreeze Pub in Kisumundogo Village, Kibera. Once an active bar and restaurant, the Railbreeze is now an empty hut where Kenyan youth pass the time. Idleness is considered one of the greatest threats to peace and stability in the slums; therefore, many youth groups have formed with the sole objective of providing a productive outlet for adolescents. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Members of the Gange Youth Self Help Group in Kibera gather trash and transport it to a local dump site four to five times a day. Gange, which means "hard working," was started in 1996, and was the first youth reform project to take root in Kibera. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Moses Omondi, 30, is pictured with friend and Chief Campaign Manager Joan Limbala in Kibera. Omondi currently serves as an elected Youth Leader at the sublocation level for youth in Kisumundogo, one of Kibera's many villages. With Limbala's help, Omondi hopes to be elected to the position of County Representative for Makina County in 2012. If elected, Omondi will represent Kibera as a new constituency before the governor, alongside two to four other representatives. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Youth worker Moses Omondi teaches young children ages 13-16 about inner peace and how to respond to violence at a weekly Peace Club meeting at St. Juliet School. As a project of Tatua, which means "to solve," Peace Club was started in March 2011 to give Kenyans the tools and knowledge necessary to live at peace with oneself and among others. "We are teaching the young generation about the issues that can disturb peace," said Martin Musambai, a volunteer with Tatua. "They need to know how to safeguard themselves against a life of violence. If you target the children, give them the skills, when they are adults they will be able to resolve their own conflicts." ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Kamau "Kelly" Nganga, 22, walks through a predominantly Luo section of Kibera slum. Following the post-election violence of 2007/2008, many Kikuyu Kenyans were forced out of the slum by other tribes and forced to resettle in rural areas. Nganga, a Kikuyu, was protected by his involvement with Youth Reform, and is now one of the few Kikuyus left in Kibera. As a boxer with the Kibera Olympic Boxing Club, the fact that Nganga, a Kikuyu, represents the slum has been a surprise for many. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Nganga trains with handmade cement weights under the direction of coach Hassan Khalifa, a Nubian. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

In a community gym, youth await the announcement of opponents as a boxing ring is assembled. Without a sponsor, equipment and supplies for Kibera Olympic Boxing Team are in short supply. The little equipment they have is passed between teammates before each bout. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Members of the Kibera Olympic Boxing Club train for an upcoming bout in Nairobi, Kenya. As an effort to keep youth off the street and away from violence, athletic groups led by volunteer coaches have begun to form in the slums of Nairobi. ©Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

All images © Bob Miller/Alexia Foundation

Fonte

BIO

Bob Miller is a freelance photographer and multimedia journalist based in Syracuse, New York. Specializing in visual storytelling for editorial, non-profit and corporate clients, Bob implements a variety of media to give stories their most appropriate voice.

Originally educated in graphic design, Bob began photographing when he discovered his love for the photographic essay. Since 2006, his work has drawn him to Kenya, Sudan, Bolivia, Mexico and the United Kingdom, and has been recognized by the College Photographer of the Year competition and recently exhibited at the Getty Images Gallery in London. As a freelance photojournalist, Bob has covered human interest and conflict stories and has documented international music tours for clients such as Universal Music Group. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, the Christian Science Monitor and Southern Living Magazine.

Bob graduated with a BA in graphic design with a cognate in journalism from Samford University, and is currently completing a masters degree in multimedia storytelling from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. He and his wife Allison live in Syracuse, NY.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento