The Caucasus is not Asia. Neither is it Europe nor the Middle East. It is its own world. Packed into the geographical boundaries of several nations, more than 50 ethnic groups carve out life the craggly mountains. The northern section: Chechnya, Ossetia, Kabardino- Balkaria, Adygea, Ingushetia, and Dagestan, currently all part of the Russian Federation, have a long-running history of religious, political and military conflict from tsarist times to the present.

In recent history, two ferocious wars in Chechnya in the 1990s resulted in high casualties, long-term psychological scarring, and a deep-rooted sense of foreboding toward the entire region. While that conflict may have subsided, others have arisen. Most notably, in the republic of Dagestan, recently named the most dangerous place in Europe by the BBC. Here Russian Federal forces fight an increasingly horrific campaign against an insurgency increasing in size and tenacity.

Behind it, the self-styled Mujahideen leaders of the “Caucasus Emirate” claim responsibility. They have declared jihad to establish strict Sharia law. It is the latest installment of struggle for the region.

This jihad is not a traditional war with opposing sides and front lines. It rears its head temporarily then disappears. More than anything, the idea of the Caucasus Emirate blankets the region in fear of violence. Ordinary people are forced to go about their daily lives looking over their shoulders. Ironically, many feel secure only in the brief moments following a fresh outbreak of violence. My project looks at the psychological state of these people, who grow up in the historical chain of conflict and violence. What is it like never to have felt safe?

Dagestan is the most ethnically diverse of the Caucasus republics. It was the entry point of Islam into Russia in the 8th century. It is considered the hideout for the leaders of the Caucasus Emirate. These factors have made it the most difficult and the thus most underreported republic in the mountain range. It is nearly impossible tell whether any progress toward peace has ever been made there.

Away from the headlines, the conflict takes its toll on ordinary people. Every month brings new disappearances and murders. Often, the family members claim their loved ones have no connection to the militants, and it almost always remains unknown what, if anything, they have done to deserve such harsh punishment. There is no rhyme or reason to the pseudo-judicial executions, as if a misplaced word here or there, is sufficient invitation for a visit by a shadowy squad of armed men.

For over a year I have been traveling to Dagestan to document the stories of women who have lost sons and husbands to the conflict. My work is done with a local Dagestani NGO called “Advocacy” who are dedicated to stopping violence and dealing with the effects of its aftermath. Through them I am able to get to the heart of the complex issues. Like Advocacy, but with my photos I am trying to put a human face on the conflict in the hopes of stopping it. Through the use of my photographs the head of Advocacy Gulnara Rustama has been able to open a centre for widows of militants who face discrimination.

With the support of the Alexia fund, I would be able to push this story to the next level. With new skills and knowledge and by harnessing modern technology I could bring larger international attention to this diverse culture and its intertwining conflicts. And somehow, begin to comprehend how these tenacious peoples survive through it all.

KIROVAUL, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: Dagestani women who have lost male family members in armed conflict sit on a couch on November 24, 2010 in the small village of Kirovaul, Dagestan, Russia. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterised by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

BALAKHANI, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – MAY 2011: The sacred place Aisha-Khur near the village Balakhani. Oxana Onipko

KIROVAUL, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – FEBRUARY 2011: A Dagestani man who asked that his name be withheld walks through a cemetery on February 21, 2011 in Kirovaul, Dagestan, Russia. The man was visiting the grave of his son who was killed in unclear circumstances. Oxana Onipko

MAKHACHKALA, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: A ram is skinned after being sacrificed during the Eid al-Adha holiday on November 18, 2010 in Makhachkala, Dagestan, Russia. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterized by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

KIROVAUL, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: A Dagestani woman holds a telephone with a picture of her husband who was killed in unknown circumstances on November 24, 2010 in the small village of Kirovaul, Dagestan, Russia. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterised by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

KIROVAUL, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: Dzhenet Achalimova, 25, stands beside her two children in her bedroom on November 24, 2010 in Kirovaul, Dagestan, Russia. She claims her husband, Magomed Nasibov, 31, along with his cousin were abducted and killed by men in camouflage in Makhachkala, Dagestan. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterised by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

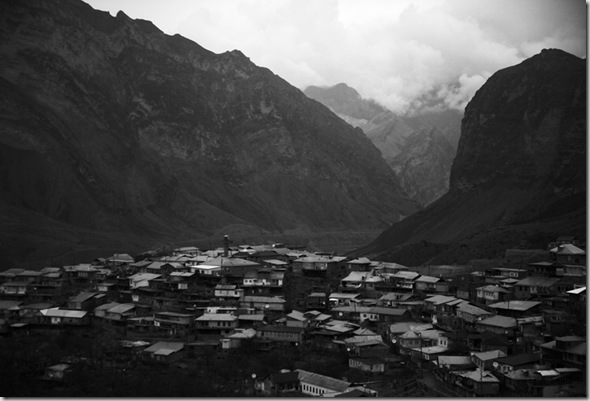

GIMRY, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA - MAY 2011: A view of Gimry nestled in the mountains on May 2, 2011 in Dagestan, Russia. Muslims in Gimry practice the “Sulafi” doctrines and teachings, widely considered to be extremist in Russia. Oxana Onipko

MAKHACHKALA, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: Aishat Dzhavatkhanova, 57, visits the grave of her son on November 23, 2010 outside Makhachkala, Dagestan, Russia. Her son was abducted and killed in unclear circumstances in June 2009. He was 27. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterized by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

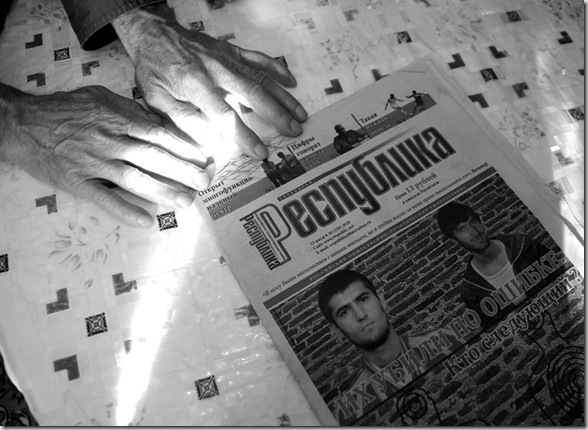

KIROVAUL, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – NOVEMBER 2010: Local Dagestani newspaper shows the images of two missing men with the headline "They were killed by accident, who's next?" on November 24, 2010 in the small village of Kirovaul, Dagestan, Russia. Dagestan, near the Chechnya zone of armed conflict in the violent Caucasus mountain region, is stricken with a low-scale guerrilla war, a painful and complex conflict characterised by the assassination of officials, police, and religious leaders, the abduction and murder of peaceful Muslims and suicide bomb blasts. Oxana Onipko

BALAKHANI, DAGESTAN, RUSSIA – MAY 2011: Local school teacher Rasul Magomedov speaks at his home on May 2, 2011 in Balakhani, Dagestan, Russia. One of Magomedov’s daughters, Mariam Sharipova killed herself and numerous bystanders by exploding a bomb in the 29 March 2010 suicide metro bombings. Magomedov has been declared missing since November 2011. Oxana Onipko

All images © Oxana

Onipko

BIO

Oxana Onipko, b. 1980 in eastern Ukraine, is a Russian photographer based in Moscow focusing on the contemporary social issues of the former Soviet Union. After four years in finance, Oxana decided to pursue a career in photojournalism and documentary photography. She likes the fast pace of daily news as well long-term documentary work. Oxana’s work is based on the principles of humanism.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento