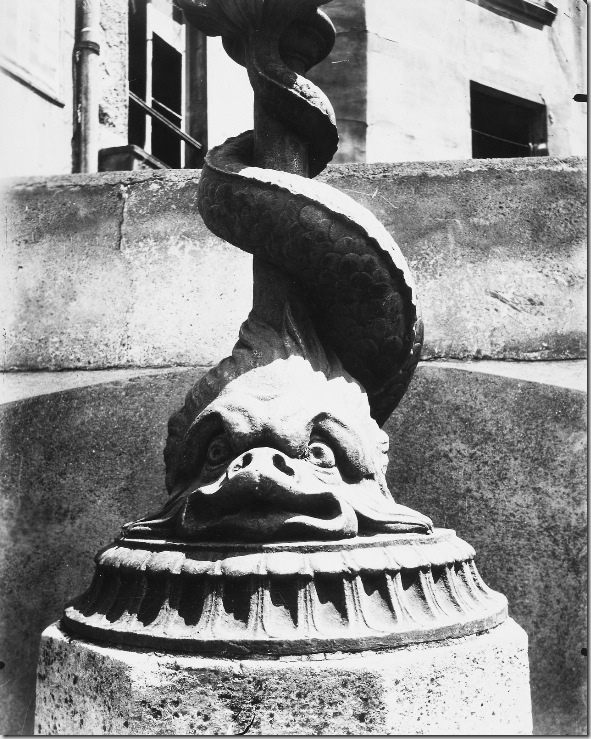

By 1891 Atget had found a niche in the Parisian artistic community selling to painters photographs of animals, flowers, landscapes, monuments and urban views. In 1898 he began also to specialize in documents of Old Paris, to satisfy the popular interest in preserving the historic art and architecture of the capital. Working alone, Atget accumulated a vast stock of photographs of old houses, churches, streets, courtyards, doors, stairs, mantelpieces and other decorative motifs. He marketed these images not only to artists but also to architects, artisans, decorators, publishing houses, libraries and museums. While Atget made his name doing this work, much of his production was routine; his artistic fame came from his pursuit of this approach.

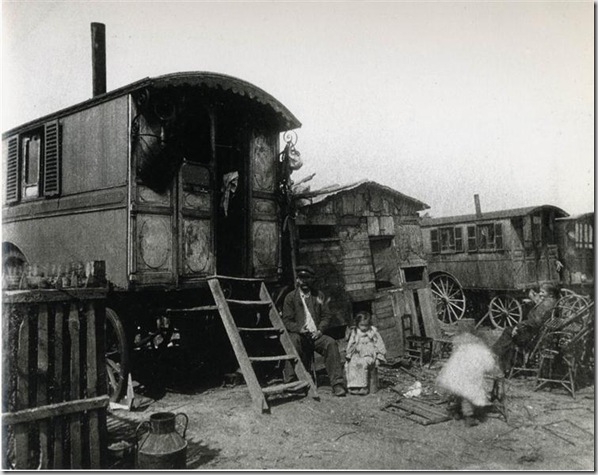

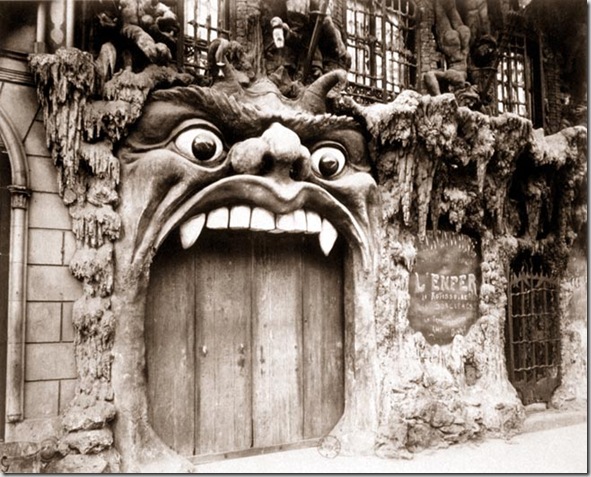

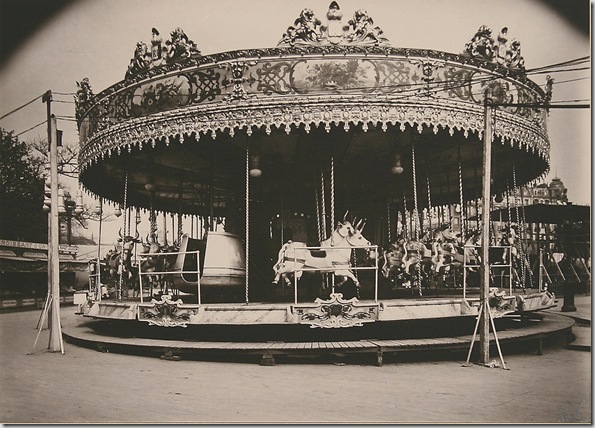

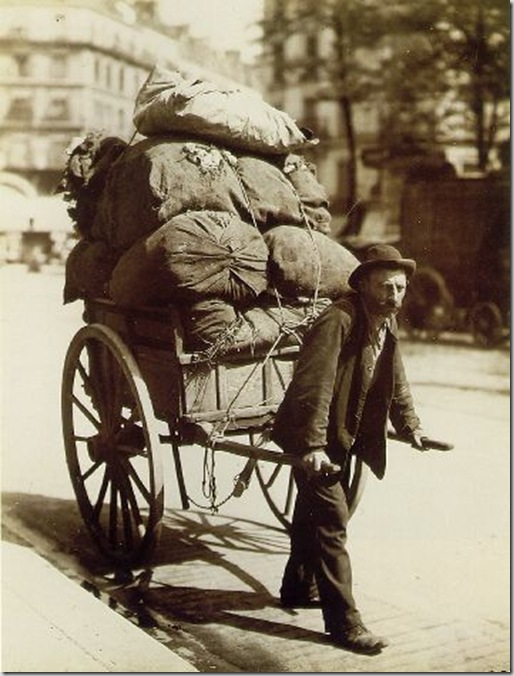

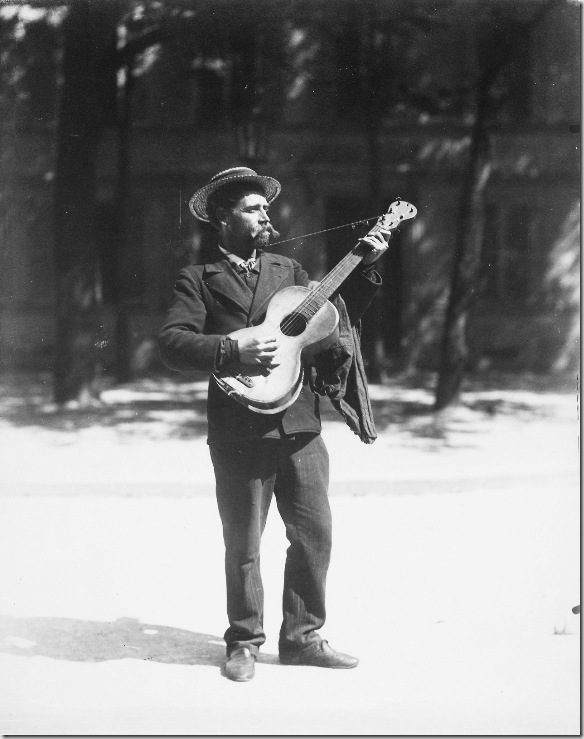

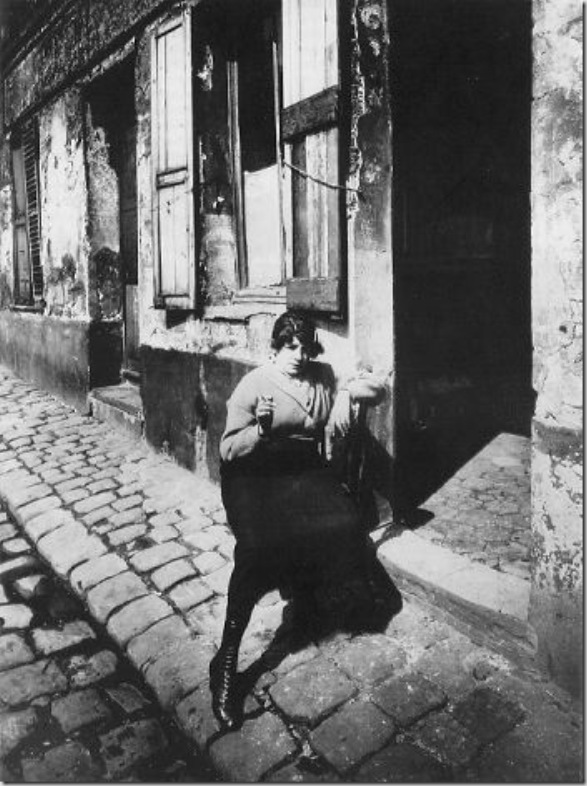

The oeuvre demonstrates this variance throughout; while Old Paris was Atget’s main theme, as he worked he occasionally made photographs that seem more picturesque, imaginative or formally inventive than others. Besides these individual, idiosyncratic pictures, Atget also made some series of related images that denote a more vivid artistic presence. These include street scenes and the petits métiers series (1898–1900); vehicles, bars, markets, boutiques, gypsies, the quais and ‘zone’ (1910–14); prostitutes, shop displays and street circuses (1921–7); and the churches, châteaux and gardens of the Parisian environs, especially Versailles (from 1901), Saint-Cloud (from 1904) and Sceaux (1925; e.g. Parc de Sceaux, March, 8 a.m., New York, MOMA).

The tendency towards personal autonomy and free expression grew more marked as Atget’s career progressed. Around 1910 he made seven carefully composed albums that he sold to the Bibliothèque Nationale (see Nesbit), and in 1912 he broke off a continuing assignment to survey the topography of the central wards of the old city for the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His pictorial production continued to fall during World War I, when he photographed hardly at all.

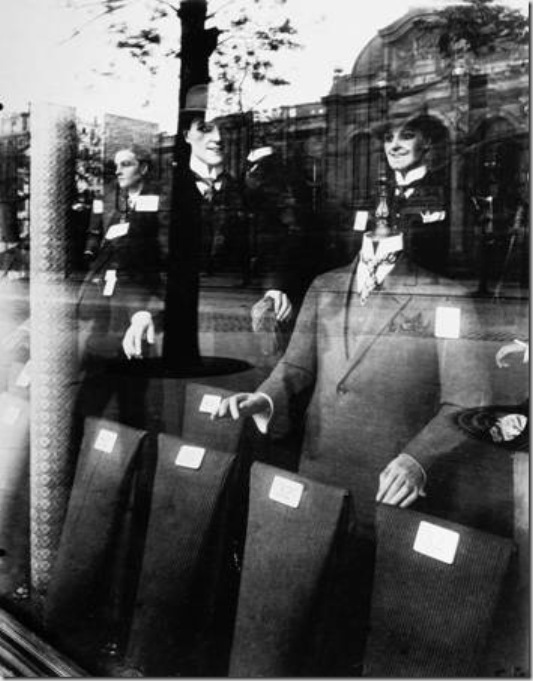

In 1920 Atget sold most of his negatives of Old Paris to the government; he had completed that section of his work. While he retained an interest in the same genres of subject-matter thereafter, he increasingly chose different aspects to depict. Whereas his energies had been channelled into the relatively methodical production of good, serviceable documents from 1898 to 1914, from 1922 until his death Atget more often made pictures whose usefulness as reports to architects or decorators was questionable. The metaphorical power, suggestive mood and pictorial innovation in the late work appealed rather to an audience of poets and painters such as Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, Robert Desnos (1900–45) and other Surrealists, who hailed the photographer as a ‘naive’ whose straight yet sentient attitude had analogies with their own.

In fact Atget’s art has little to do with Surrealism; it expresses his acutely intelligent assessment of what he valued through the medium of photography. The early morning light on a Parisian street, the palpable atmosphere enveloping a pool at Saint-Cloud and the disarming gesture of a mannequin reflected as if in the street on a shop-window, were as directly and unselfconsciously apprehended and with the same seriousness, humility and humanity as the door-knockers and apple trees photographed early on. If the late works reveal the artist’s own sensibility as much as the ostensible motif, it was not Atget’s idea of his function that had changed but his vision of what was worth photographing.

Atget’s best work is a poetic transformation of the ordinary by a subtle and knowing eye well served by photography’s reportorial fidelity. His transcendent, haunting works transposed photography’s function from the arena of 19th-century commercial documentation into the realm of art. This legacy, posthumously heralded as paralleling the rejection by ‘art’ photographers of Pictorialism and the return to the straight, unmanipulated approach, passed into the tradition of modern photographic history through the efforts of the American photographer Berenice Abbott, who met Atget in 1925 and who acquired his estate at his death. It is now owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Maria Morris Hambourg

From Grove Art Online

© 2009 Oxford University Press

Fonte

La scelta dei soggetti, la qualità visiva, il rigore della composizione, il senso della luce e la valorizzazione di tutto ciò che è banalità. Noto come “il fotografo di Parigi”, colui che con un’enorme mole di fotografie (oltre 10.000) lungo l’intero arco della sua oscura vita, aveva instancabilmente registrato nei minimi dettagli gli aspetti più quotidiani di una metropoli che stava mutando, Eugène Atget è in realtà ben altro che il documentatore d’insoliti e pittoreschi angoli della sua città; egli è il primo fotografo a liberarsi totalmente dalle convenzioni del Pittorialismo, per dare alla sua professione una nuova dignità, acquisita solo con i mezzi del suo specifico tecnico. E’ il primo fotografo nell’accezione moderna del termine, oltre che un reporter sociale ante litteram.

Tuttavia la sua opera è sempre stata campo di battaglia per incomprensioni, lodi, biasimi e quant’altro. Fu classificato nel genere pittoresco ed aneddotico mentre la sua fotografia plastica costituisce il più importante memoriale vivente di una città, la sua Parigi.

Ma se le sue immagini del popolino parigino nella vita quotidiana, seduto nei bar, dedito all’artigianato, delle botteghe e delle vetrine hanno un posto importante. Lo hanno altrettanto le immagini del volto della Parigi di un tempo, con le sue strade, le sue viuzze, i suoi cortili, i suoi vicoli, il paesaggio urbano che andava via via modificandosi.

La sua inchiesta fotografica lo portava a percorrere in lungo e in largo Parigi e la periferia nell’intento di ritrarre immagini del passato ancora visibili nonostante la patina del tempo e i guasti portato dagli uomini. Non si tratta del lavoro di una persona che si lascia conquistare solo dal pittoresco o dagli scontri tra luce e ombra per tradurre attraverso il tempo passato, la perennità dei secoli trascorsi. Egli ha quindi rinnovato l’immagine documentaria, forse senza esserne del tutto consapevole, e la metafora fotografica.

Se le sue immagini candide, le sue immagini specchio di verità, le sue immagini che raccontano una storia, cantano ai nostri occhi e ci commuovono in mille modi diversi è perchè il loro significato va ben al di là di ciò che rappresentano.

Ve ne sono di affascinanti, di stupefacenti, di fiabesche e tutte risuscitano un passato da lui vissuto o un passato di cui ha conosciuto solo il nome e il suo essere effimero, del quale non ha goduto e che rimpiange. Ed ecco allora le atmosfere pregne dei famosi riflessi e degli sfumati che hanno caratterizzato la sua opera, il non essere, ma volerne inutilmente, esserne parte.

Fonte

Eugène Atget: Eclipse, 1911

Eugène Atget: Eclipse, 1911

After the Great War, Atget frequently focused on mannequins, statues, and other “substitute” actors. At Versailles, where he had worked since 1901, he came to see the sculptures not as felicitous ornaments but as characters in an immemorial play. In this picture, which represents Michael Mosnier’s replica of the “Dying Gladiator” in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, Atget contrasts human pain and artistic beauty, mortal man and the immortal soul. Drawing on his long experience relating near and far objects and vistas in the gardens of Versailles, the photographer juxtaposed the statues so that the figure of Apollo in the background seems to rise like the living spirit escaping the body at death.

All images © Eugène Atget

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento