THE SOVIET SPY WITH A CONSCIENCE

The Serpentine, Hyde Park, London 1935-39

The Serpentine, Hyde Park, London 1935-39

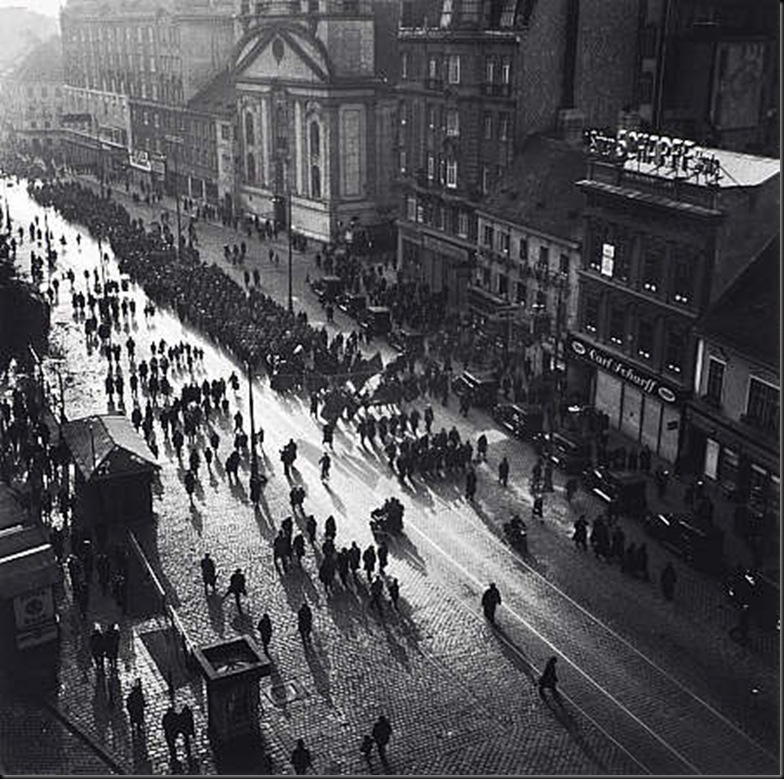

This is a very dynamic image showing members of the Social-Democratic Youth

Movement marching in Vienna. In the wake of the First World War, the Austrian

political parties had a youthful membership ? it is estimated that up to sixty

per cent of the Viennese Social Democrats were under forty years of age. The

limits of teenagers? political engagement was a particular source of

controversy, with many arguing that the youth movement should be more

educational than political. Memoirs of the period reveal that political

identification was often fluid. A common joke amongst young activists was that

you went to bed a Social Democrat and woke up a Communist!

She was, nevertheless, successful in one important regard: she is thought to have recruited Kim Philby, one of the Cambridge Five.

Children preparing vegetables at the North Stoneham camp for Spanish Civil War refugees, Hampshire, 1937 Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HART

Children preparing vegetables at the North Stoneham camp for Spanish Civil War refugees, Hampshire, 1937 Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HART

This is a captivating image showing a group of children surrounded by

cabbages that they are preparing. They are refugees from civil war-ravaged

towns of northern Spain. In May 1937 nearly 4000 children arrived by boat in

Southampton. Suffering terrible sea-sickness, they underwent medical

examination before being housed in a temporary camp at nearby North Stoneham.

Aged mostly between five and sixteen, and from both sides of the conflict, they

were to be rehoused by the Basque Children?s Committee in residential

`colonies? around the country. Refugees were settled as far north as Montrose

in north east Scotland.

May Day was the most important event in the urban calendar, a political

festival on a mass scale that validated Vienna’s status as a socialist city.

Marchers converged on the city centre, led by the powerful Austrian Social

Democratic Party. Grandstands were erected outside Vienna?s City Hall for music

and speeches, whilst the far smaller Austrian Communist Party staged a separate

demonstration in front of the Votive Church nearby. However, as political

tensions heightened May Day marches became an arena of conflict, between

different left-wing factions and an increasingly authoritarian national

government. In May 1933, the Austrian Chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, banned

demonstrations altogether, barricading off the centre of Vienna. Tudor-Hart was

arrested shortly afterwards.

Members of the Social-Democratic Youth Movement marching in Vienna (circa 1930) Credit: Edith Tudor-Hart

Members of the Social-Democratic Youth Movement marching in Vienna (circa 1930) Credit: Edith Tudor-Hart Barricade on the Operngasse, Vienna 1930-33

Barricade on the Operngasse, Vienna 1930-33In May 1933, the Austrian Chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, banned demonstrations altogether, barricading off the centre of Vienna. May Day was the most important event in the urban calendar, a political festival on a mass scale that validated Vienna?s status as a socialist city. Marchers converged on the city centre from all quarters, led by the powerful Austrian Social Democratic Party. Here, Tudor-Hart has captured a barricade on the Operngasse, a street in the centre of Vienna. The foreground is filled with barbed wire, its linear quality emphasised by the strong sunlight. In the shadow in the behind soldiers are visible.

Caledonian Market, London

Caledonian Market, LondonIn this image Tudor-Hart focuses the viewer’s attention on the two young girls who are trying to decide what to buy from the pile of clothes and shoes lying in the sun. Caledonian Market was one of the largest flea-markets in London during the 1930s. It was popular with photographers as it offered easy access to a lively aspect of the city’s working-class culture. Fellow exiles such as Bill Brandt and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy also photographed there, perhaps because it provided an echo of a complex street life commonplace on the Continent.

Caledonian Market was

one of the largest flea-markets in London during the 1930s. It was popular with

photographers as it offered easy access to a lively aspect of the city’s

working-class culture. Fellow exiles such as Bill Brandt and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

also photographed there, perhaps because it provided an echo of a complex

street life commonplace on the Continent.

No Home, No Dole, London 1931

No Home, No Dole, London 1931In a society with only rudimentary welfare payments, high levels of unemployment were one of the central political questions of the day. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Britain’s access to world markets declined dramatically, leading to heavy job losses, particularly in industrial regions. By 1931 unemployment had reached more than three million and the Labour Government collapsed, in part because it attempted to reduce benefits. This photograph is a comment on these events and perhaps particularly the problems faced by workers who had been made homeless as a result of joblessness

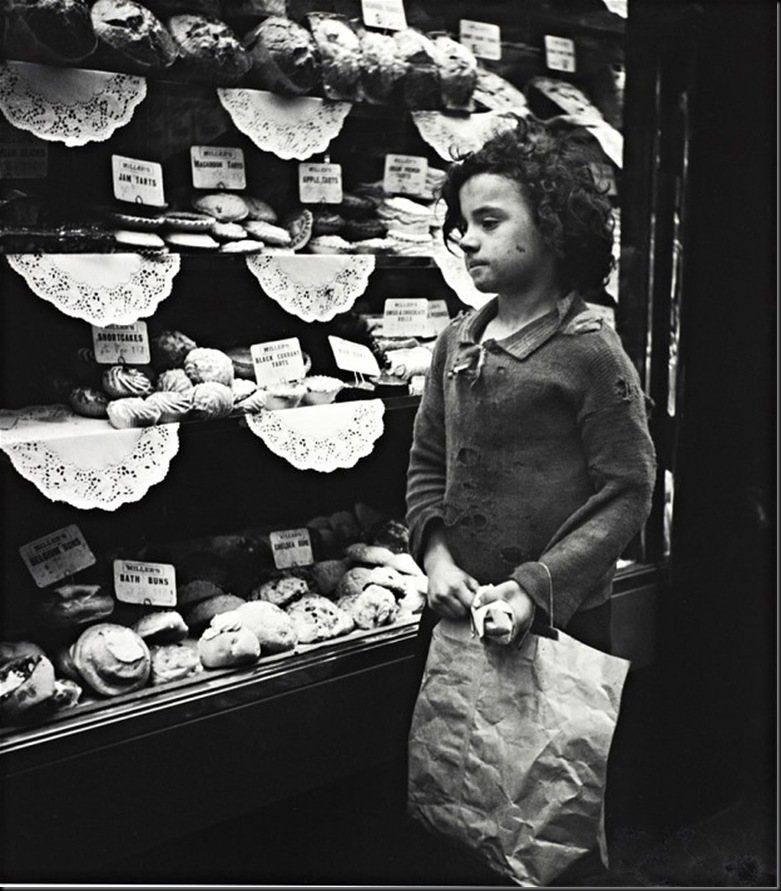

Her most popular image from the Thirties was Child Staring into Bakery Window, taken in Whitechapel, London. The juxtaposition of the plenitude of the bakery window with the dishevelled and hungry child emphasised the gap between rich and poor, and it was reproduced in a number of socialist propaganda pamphlets. It also reflected her preference for strong contrasts of black and white.

A family group in Stepney, London (circa 1932) Credit: Edith Tudor-Hart

A family group in Stepney, London (circa 1932) Credit: Edith Tudor-HartTudor-Hart worked extensively amongst working-class communities in East and North London, photographing children on the streets and families in their homes. She was part of a larger movement on the left concerned about the effect of widespread slum housing. However, Tudor-Hart’s imagery is rarely merely propaganda and her ability to connect with those she photographs ? often women and children ? is evident. This complex photograph explores the photographer’s relationship to her subjects. Shot deliberately through the window it emphasises her voyeurism, thus limiting the sentimental impact of the image.

Slum Housing, Vienna 1931

Slum Housing, Vienna 1931The housing question lay at the heart of the Viennese project of municipal socialism. Facing a collapse in the housing market after the First World War, the social-democratic administration built nearly 64,000 new homes between 1919 and 1934, providing accommodation for around 200,000 people. The programme was the envy of Europe and was frequently praised by British Labour politicians. However, whilst impressive, the number of homeless in the city continued to rise, tripling between 1924 and 1934. This is one of a series of photographs by Tudor-Hart of a city slum, suggesting she was keen to document an aspect of Viennese life too often avoided by official publications.

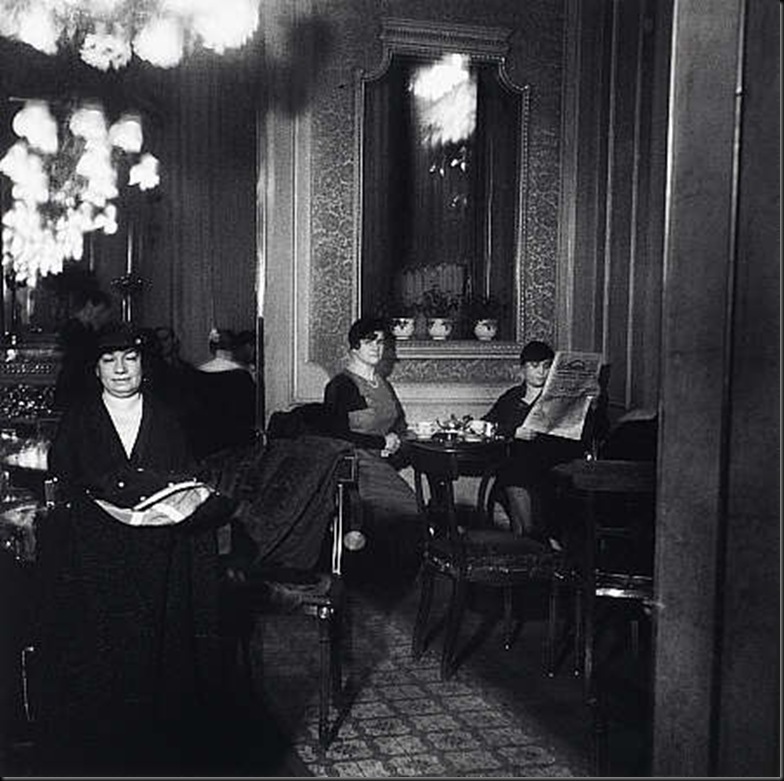

Cafe Interior, Vienna 1932

Cafe Interior, Vienna 1932The location of this cafe is something of a mystery, although it clearly evokes the comfortable self-containment that many historians have argued was a defining feature of Viennese modernity. The city’s celebrated cafe culture was at once a refuge from a difficult world and also a space where individuals could linger for hours, talk, write and read a selection of newspapers. If there is something unusual about Tudor-Hart’s view, it is that she shows a public space, often associated with male artists and intellectuals, as dominantly occupied by women.

Ultraviolet light treatment for children with rickets in a south London hospital (circa 1935) Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HART

Ultraviolet light treatment for children with rickets in a south London hospital (circa 1935) Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HARTThis photograph was taken for a booklet promoting the work of the South London Hospital for Women and Children, produced in collaboration with the German exile photographer, Grete Stern. Its shows light treatment for children suffering from vitamin deficiencies, a standard cure at the time. The South London Hospital was founded in 1912 ?to meet the growing demand of women for medical treatment by members of their own sex?. Tudor-Hart campaigned throughout her life for health reforms for women and children, part of a wider movement of women whose activity was vital to the formation of the National Health Service in 1948.

Swastikas in Shadow, Vienna 1932

Swastikas in Shadow, Vienna 1932The precise date and location of this photograph are hard to pin down, but its meaning ? a sign of the gathering Nazi threat ? is unmistakeable. The Austrian Nazi Party grew in strength from the early 1930s, largely in response to a sharp downturn in the economy. It proved particularly popular amongst young people, many suffering long-term unemployment. In 1933, the Austrian Chancellor banned the Party imprisoning many of its activists in concentration camps. Tudor-Hart’s photograph eloquently points to the growing significance during the 1930s of anti-fascist politics for both the Austrian and British left.

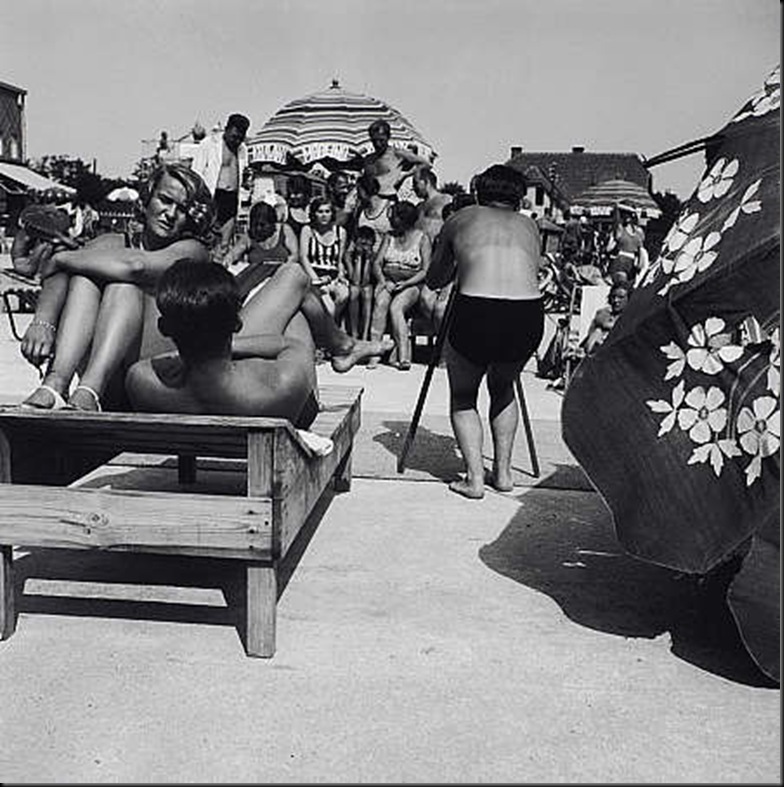

Lido, Modling, near Vienna 1932

Lido, Modling, near Vienna 1932Modling, to the South of Vienna, was a popular weekend resort with good bathing facilities and easy access to nature. With a working-class population suffering high levels of disease, and in particular tuberculosis, municipal bathing was a political priority for Viennese authorities. By 1927 public swimming pools in Vienna received nine million visits. It was still rare, however, for municipal housing to be built with private bathrooms. The comparative novelty of photography as a mass leisure pursuit was also something Tudor-Hart felt it important to document. Shown here by the family posing for a group photograph.

The unemployed demonstrate in Vienna, 1932 Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HART

The unemployed demonstrate in Vienna, 1932 Photo: EDITH TUDOR-HARTThroughout the 1920s Vienna was afflicted by high levels of unemployment, a source of social unrest. Some estimates suggest that by 1933 this affected as many as 750,000 people, or forty percent of the urban labour force. The social-democratic administration worked hard to alleviate unemployment’s worst aspects, paying special attention to working-class housing and cultural provision in the city. However, they did little to resolve inequality and the social-democratic leadership was frequently accused of valuing cultural over political and economic struggle. Tudor-Hart photographed both the effects of unemployment and the Social Democrats’ efforts to improve the lives of the city’s working class. Her images reflect the stark contradictions of interwar Vienna.

Refreshment Kiosk, the Lobau, Vienna 1932

Refreshment Kiosk, the Lobau, Vienna 1932The Lobau, an area of water and forest to the east of Vienna, was promoted by the Social Democrats as a place of healthy recreation for the city’s working class. In 1932, Tudor-Hart contributed to a photo essay on the Lobau in the illustrated magazine `Der Kuckuck’. Titled `Wildbaden in der Lobau’ [Free Bathing in the Lobau], the essay emphasised that an area that was once a playground of the imperial monarchy was now open to the people of Vienna. This photograph was captioned `Kurhotel Lobau’ [Spa Hotel Lobau], an ironic reference to the facilities previously enjoyed only by Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia.

Had she not been arrested in Vienna in 1933 – for being a Communist sympathiser – she would probably have remained there. Instead she escaped imprisonment by marrying an English doctor and was exiled to London. “When she moved from Vienna to Britain she moved away from Bauhaus-style social realism to a more emotional identification with the figure in the picture,” Forbes says. “Her work became more direct and affecting. It can’t have been easy being a German-speaking émigré in wartime Britain. I think the move meant her life became a struggle.”

All images © Edith Tudor-Hart

Fonte

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento