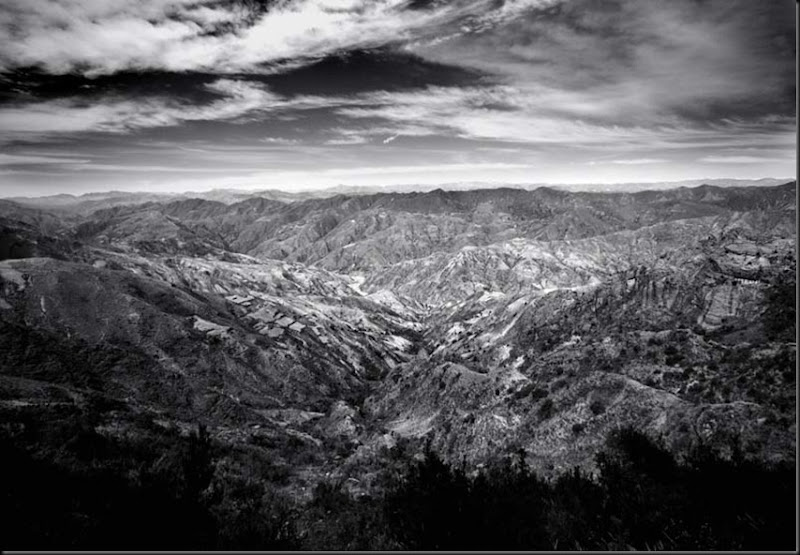

“Toro-Toro” is declared national park and protected area in 1989. In the north of the Department of Potosi, Bolivia, an area of around 150 Km squared stretches itself between the rocks and in its drawings, in the caves and waterfalls, in the ancient rocks paintings. An area covered by dinosaurs’ footprints who once populated massively this region, today with an immense geological and anthropological potential, wild and rich in fauna, Mesozoic Jurassic park between 1.800 and 3.800 metres above sea level.

Valleys and mountains here are as magic as, in some ways, hostile towards the Quechua communities (one of the 36 Bolivia’s ethnicities) populating today the region of Toro-Toro; the poor lands’ fertility and the seasons regulate local production, based on potatoes and a few cereals; farming is the economic activity mostly diffused: donkeys, cows, sheep and goats populate valleys, in constant search of water and food. The isolation of many communities is indeed extreme, as many of these can be reached by foot, only after hours walks. The weather can become unforgiving according to altitudes. There is almost no electricity in the region (except for a few solar panels installed by some cooperation project) while water – the blood of the Pachamama according to the Andean Cosmo-vision - is equally scarce, for everyone, humans, plants, animals. Rainfalls are every year delayed and more scarce, and Bolivia is one of the countries most severely affected by climate change.

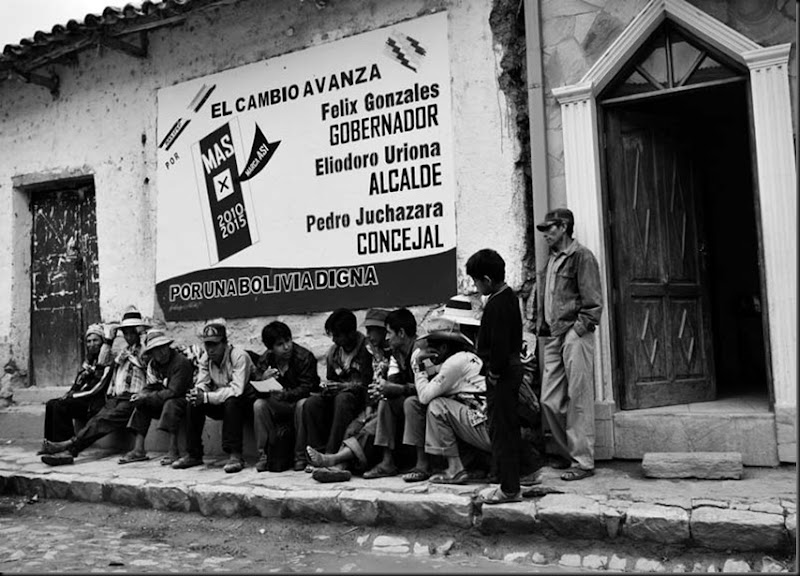

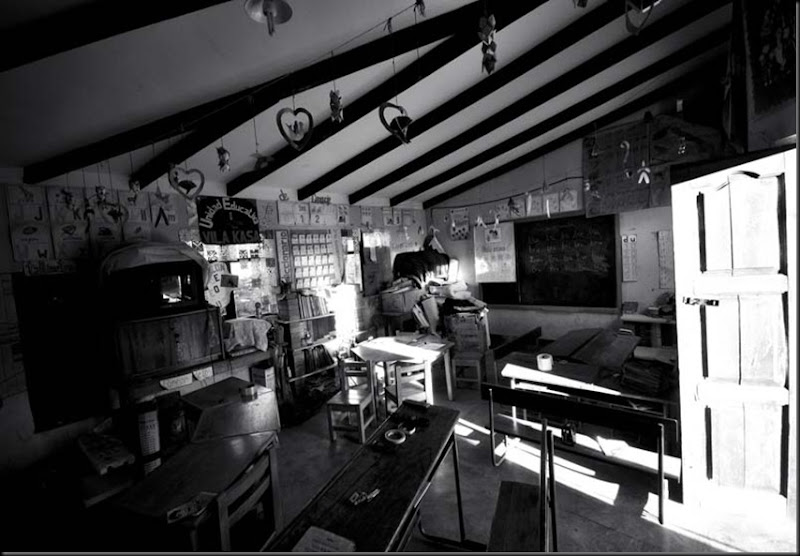

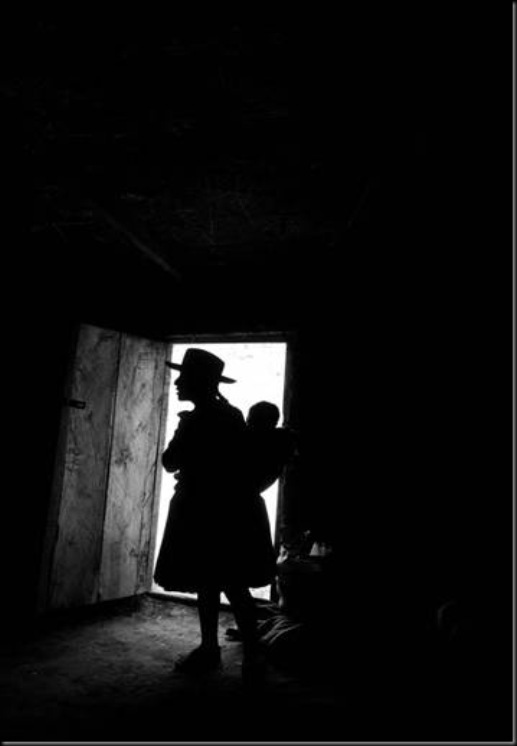

In a country like Bolivia, undergoing a process of profound political and social change, under the firm guidance of its fist democratically elected indigenous president – Evo Morales – still exist realities which seem frozen in time, partially excluded from the pros and cons of modernity. Descendants of the Inca empire, for whom Spanish is still a mostly unknown language, forced to migrate towards urban settings in search of better opportunities, they leave behind women and children; for these latter groups remain small and poorly equipped communitarian schools. Houses are simple and made of rocks, which are abundant in the landscape; poorest families share a single construction with one room, maybe 4 squared metres, where a standard family unit of 6 people can live (mother, father, 4 children).

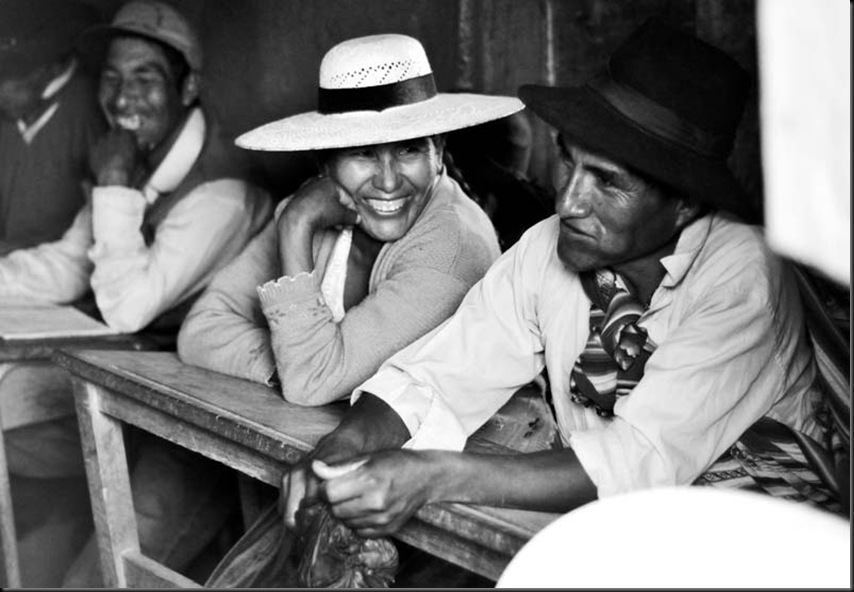

The disparities and differences between men and women with regards to daily life are, as often happens, profoundly marked. Men – often heavy drinkers but sure always chewer of coca-leafs (jealously carried in typical plastic bags always accompanying them) – take care of animals and farming fields, as well as of other “heavy” daily works. Women, on the other hand, are devoted to cooking all day long (for the whole family even if they are the last ones to eate), to the care of the always numerous children, to the care of the goats, to recollecting woods around, and to all that is required, with exhaustion permanently tattooed in the eyes. What women and men have in common are coarse hands, faces marked by time and wind, teeth consumed by constant coca-chewing, and the shared hope for a better future for their communities. In a timeless place, from the dinosaurs’ age until the XXI century, the powerful Mother Hearth – albeit tired – remains undisputed queen in Toro-Toro, and the Quechua communities share with her space and time, both in constant search for a delicate equilibrium, both fighting for a more just existence.

All Rights Reserved © Matteo Bertolino 2013

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento